CATECHESIS Q & A: Deepening Our Knowledge

We have created this section on our website and in our bulletin for the purpose of presenting Church teaching in an easy-to-understand forum. When space permits in the Parish Bulletin, we will present a new Question and Answer there about some topic of our Catholic Faith in order that each of us may understand Church teachings better and be able to share our beliefs with others.

Various members of the parish staff, along with the Carmelite Friars, have submitted these articles (including articles written by well-known Catholic apologists). These articles will be kept in this section of the website so that you may refer back to them.

God bless!

CATEGORIES: So that you may more easily find the answers to your questions, the categories (in alphabetic order) into which these articles fall are listed to the right. Some articles appear in more than one category.

The titles of the articles can be seen below; they are listed in the order of publication in the bulletin.

by Ruben Beltran

"I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?"

Matt. 3:14

"Why was Jesus Baptized?" Every January the Church celebrates the Baptism of Jesus Christ, an event recorded in all four Gospels. But the question is often asked, “Why was Jesus Baptized?” Baptism, according to the Catechism of the Catholic Church (Paragraph 1279), “…includes the forgiveness of original sin and all personal sins, birth into new life by which man becomes an adoptive son of the Father, a member of Christ and a temple of the Holy Spirit.”

But Jesus was sinless and is eternally the Son of the Father. Even John the Baptist seems confused by what Jesus did. “John would have prevented Him, saying, ‘I need to be baptized by you, and do you come to me?’ But Jesus answered him, ‘Let it be so now; for thus it is fitting for us to fulfill all righteousness.’ Then he consented” (Matt. 3:14-15). In the context of Matthew, “righteousness” is a fulfillment of the Law.

So why was Jesus Baptized?

Emeritus Pope Benedict the XVI explains it beautifully: “The Significance of this event could not fully emerge until it was seen in light of the Cross and Resurrection. Descending into the water, the candidates for Baptism confess their sin and seek to be rid of their burden of guilt. What did Jesus do in this same situation? …Looking at the events in light of the Cross and Resurrection, the Christian people realized what happened: Jesus loaded the burden of all mankind’s guilt upon His shoulders; He bore it down into the depths of the Jordan. He inaugurated His public activity by stepping into the place of sinners. This inaugural gesture is an anticipation of the Cross……

The whole significance of Jesus’ Baptism, the fact that He bears “all righteousness,” first comes to light on the Cross: The Baptism is an acceptance of death for the sins of humanity, and the voice that calls out “This is my beloved Son” over the baptismal waters is an anticipatory reference to the Resurrection” (Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth, Vol. 1).

For further reading on the Baptism of Christ see Catechism of the Catholic Church (Paragraph 536).

Published in the 1/11/15 bulletin

Excerpted from “What’s The Smoke For?” by Johan Van Parys

When you love someone, do you see it as an obligation to spend time with them?

Is it a Sin to Miss Mass on Sunday? Do we as Catholics still believe we are “obligated” to “Keep Holy the Sabbath Day”? And why are there other days of “Holy days of Obligation”? When you love someone, do you see it as an obligation to spend time with them? Or, would the person who has been saved from drowning or a fire ever think it is a burden to thank their savior? These questions bespeak a legalistic and minimalist approach to the celebration of the mysteries of our faith, which is rather regrettable and supremely sad.

Our current understanding of Sunday and holy days of obligation is that it has been imposed on us by the Church, and rightfully so. By contrast, the early Church had no such law because there simply was no need for it. The sense of “obligation” early Christians felt to celebrate Sunday Eucharist flowed from a deep personal and communal desire. Theirs was an inner obligation to celebration of the Eucharist. St John Paul II in his apostolic letter Dies Domini (On Keeping the Lord’s Day Holy), calls it “obligation of conscience”. As this “obligation of conscience” or inner desire started to wane, individual bishops found it necessary to remind the faithful that the Sunday assembly was not simply an option but rather a sacred duty. In 1917 the Code of Canon Law 1247 defined the obligation to celebrate Eucharist on Sundays and Holy days of obligation as universal law.

CCC 2181: The Sunday Eucharist is the foundation and confirmation of all Christian practice. For this reason the faithful are obligated to participate in the Eucharist on days of obligation, unless excused for a serious reason (for example, illness, the care of infants, etc.) or dispensed by their own pastor. Those who deliberately fail in this obligation commit a grave sin.

Published in the 1/18/15 bulletin

by Ruben Beltran

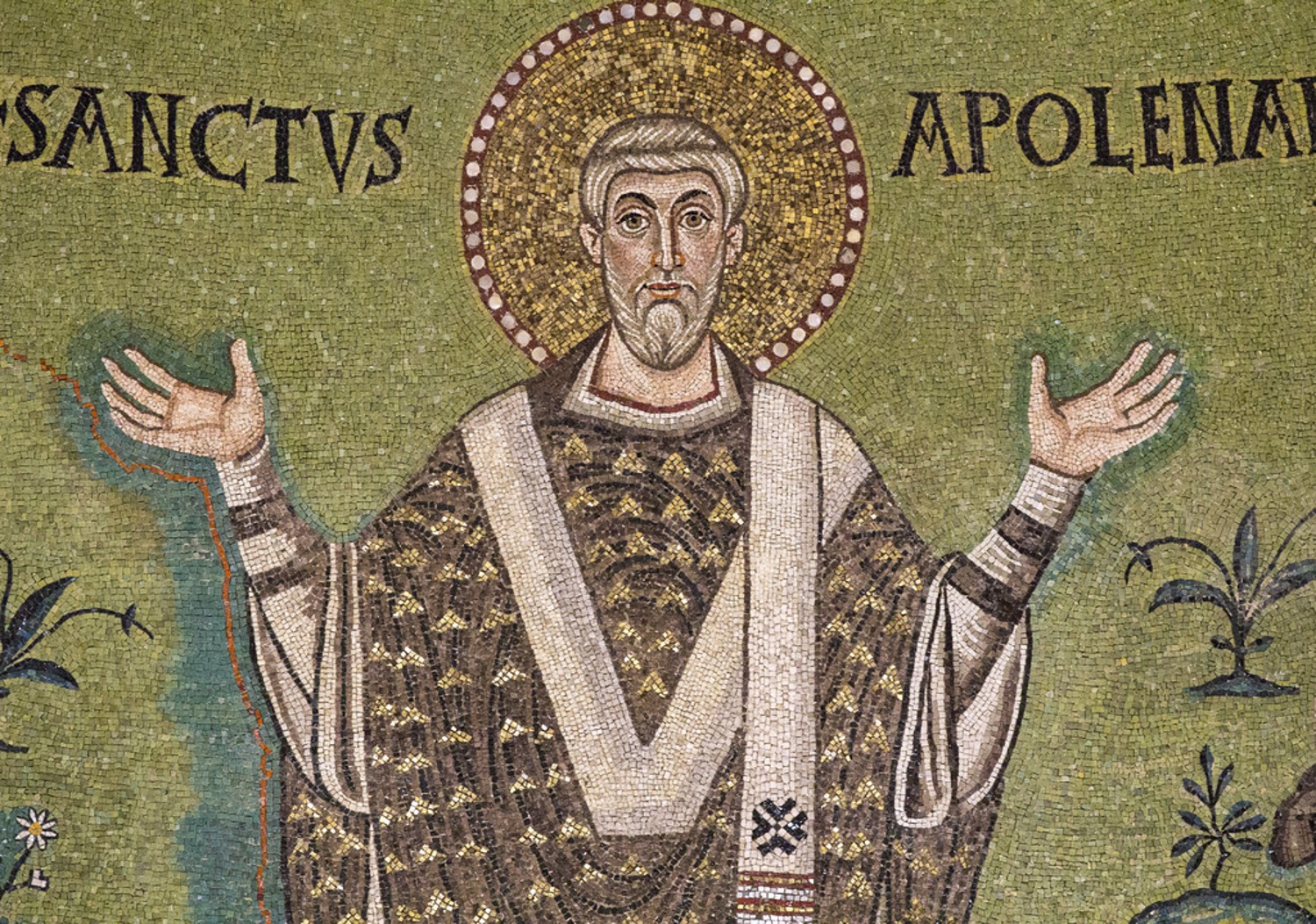

Why do Catholics pray to the Saints? Why not pray directly to Jesus? This is a question Catholics often get asked; unfortunately, most Catholics do not know how to answer. First and foremost, we need to look at what the Church teaches on the subject, and for that we turn to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, Paragraph 2683: The witnesses who have preceded us into the kingdom, especially those whom the Church recognizes as saints, share in the living tradition of prayer by the example of their lives, the transmission of their writings, and their prayer today. They contemplate God, praise Him, and constantly care for those whom they have left on earth. When they entered into the joy of their Master, they were "put in charge of many things." Their intercession is their most exalted service to God's plan. We can and should ask them to intercede for us and for the whole world.

The first thing that needs to be pointed out is that we do not pray to the saints in the same manner that we pray to God. God alone has the power to grant or deny our petitions. When we pray to the saints we only ask for their intercession; in other words, we ask them to pray for us. Some may object that the Bible says that there is only one mediator between God and man, Jesus: "For there is one God, and there is one mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus" (1 Tim. 2:5).

This is true. However, most non-Catholics have no problem asking a family member or friend to pray for them; and asking one person to pray for you in no way violates Christ’s mediatorship. Why not? Dr. Scott Hahn points out that: “First, the Greek word used here for 'one' is eis, which means 'first' or 'primary,' not monos, which means 'only' or 'sole.' Just as there is one mediator, there is also one Divine Sonship, which we all share—by way of participation—with Christ.” Because we are all part of the one Mystical Body of Christ, we share in His roles and participate in them.

Finally, some may say, ”The saints are dead; they cannot hear you and the Bible forbids communicating with the dead” (for example, Deuteronomy 18:10-11), but necromancy was the practice of conjuring up the dead through wizards or mediums in order to manipulate the spiritual realm or foresee the future, which is categorically different from asking our brothers and sisters in Christ who have passed on to pray for us.

Furthermore, the Book of Revelation shows that the saints in Heaven are clearly aware of what is happening on earth (Rev 5:8, Rev 6:10). Scripture says we are surrounded by a great cloud of witnesses (Hebrews 12:1). These are the saints who have "run the race" here on earth and are now cheering us on in Heaven. They are perfected in love because they are in the presence of God—who is Love. To love is to will the good of another, and that is what the saints do. They will that we attain the greatest good of all: God. That is why we ask them to pray with us and for us.

Published in the 1/25/15 bulletin

By Denise Holguin-McMaster, Parish Secretary

“How Should I Prepare to Come to Mass?”

Preparing to attend Mass should begin at home. First, each person who

plans to receive Holy Communion must observe the fasting requirement,

which is to refrain from food and drink for at least for one hour before

receiving. Some people mistakenly believe the Church has done away with

the fasting rule; however, it is still required—though greatly

modified. Before Vatican II, Catholics were required to fast beginning

at Midnight before receiving Holy Communion!

Next, it is important that we be in the proper frame of mind and truly contemplate what we are about to do. The Daily Roman Missal tells us that, in preparation for Mass, we can contemplate the fact that the Eucharistic Sacrifice is the most important event that happens each day—the most pleasing reality we can offer to God. It also recommends praying that the Holy Spirit will guide the priest’s words and actions, and that He will enlighten the members of the congregation to “open their ears” to receive the Word of God and accept its meaning. While there are many ways to pray in order to prepare for the Most Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, the point is to orient our minds toward God, to join with our brothers and sisters in the congregation, to have the right intention, and unite ourselves to the Sacrifice of Jesus.

Second, we should prepare for Mass in the way we dress—both modestly and respectfully. Sunday is a special day, and God's House is a special place; and so our clothing ought to reflect this truth. In the Scriptures we read, “Worship the Lord in holy attire” ( 1 Chronicles 16:29, Psalms 29:2, 96:9). Also, the Catholic Catechism teaches that our clothing “ought to convey the respect, solemnity, and joy of the moment when Christ becomes our guest” in Holy Communion ( CCC 1387). The exterior reflects the interior, and God definitely deserves the best we have—inside and out! This is also why altar dressings and priests’ vestments, etc., are normally the best the church can manage. However, we have to remember that our souls should also be “dressed nice,” which leads to our second question...

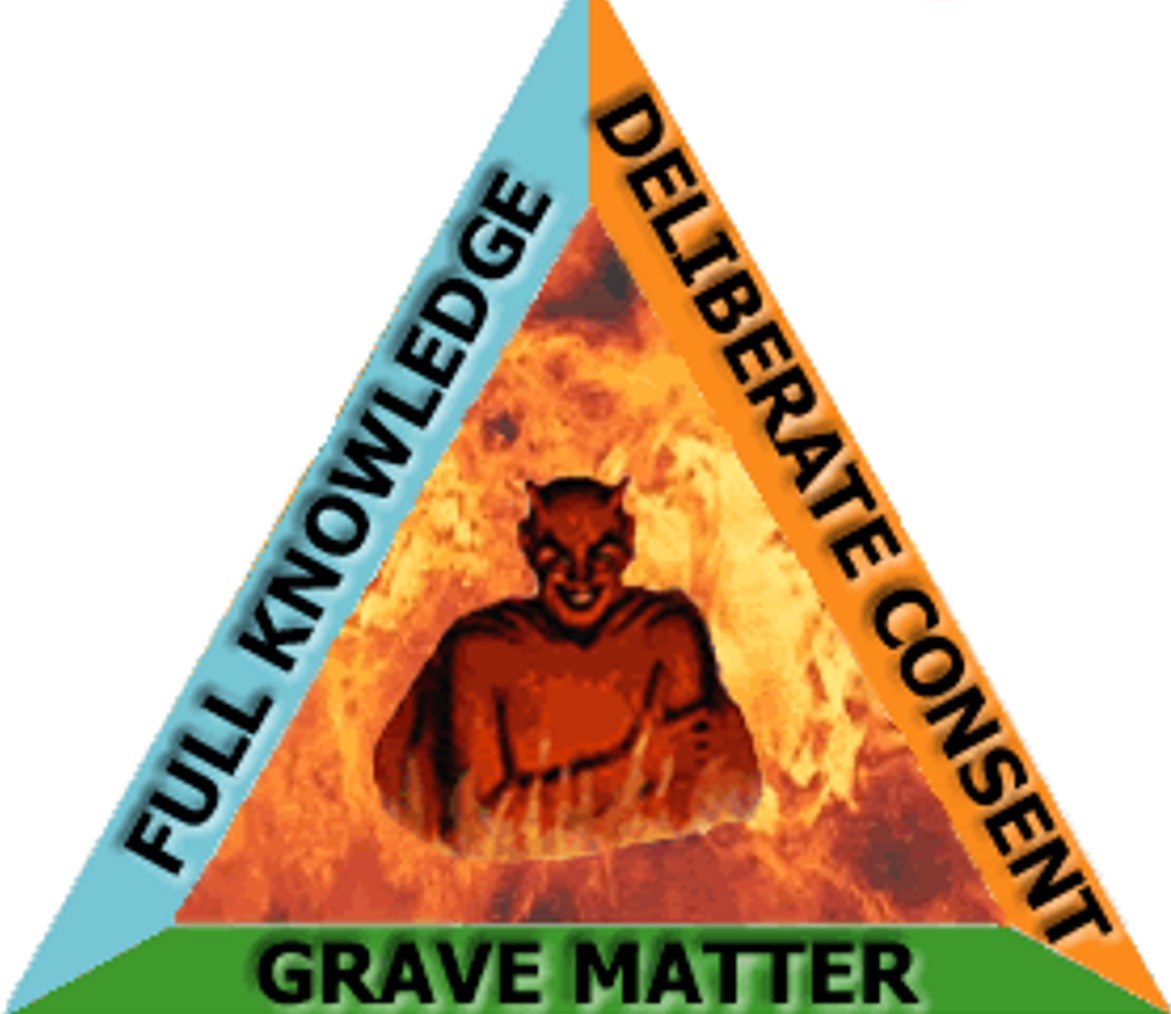

“Should I Receive Holy Communion at Mass?” In order to respond to the Lord’s invitation to eat His Body and drink His Blood, we must first examine our consciences. St. Paul says, “Therefore, whoever eats the Bread or drinks the Cup of the Lord unworthily shall be guilty of the Body and the Blood of the Lord” (1 Cor. 11:27). This means that if we have committed a serious (mortal) sin, we must not receive until we have gone to Confession. If this is the case, in lieu of receiving you may come forward and tacitly ask for a blessing by simply crossing your arms over your chest. Those who are not Catholic or who are not in full communion with the Church (professing and believing in all the Church’s teachings) are also not permitted to receive. The reason is simple: To receive while not being a practicing Catholic is to witness to something that we do not actually believe. In essence, each person who receives Holy Communion is proclaiming publicly that “I am a practicing member of the Catholic Church and I believe and follow all its teachings.”

Published in the Bulletin of February 1, 2015

By Rhonda Storey

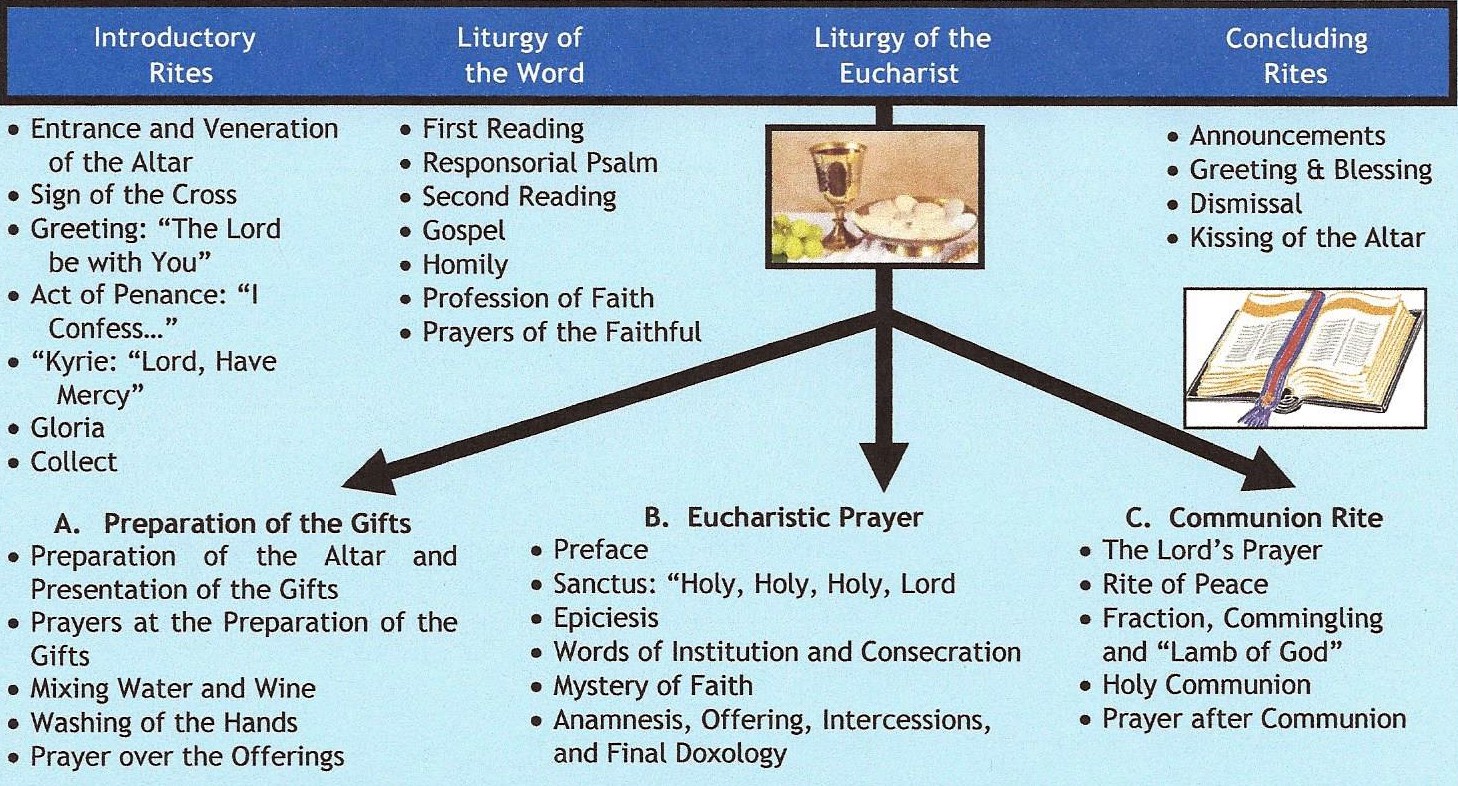

WHAT DO I MISS WHEN I COME IN LATE?

WHEN I LEAVE EARLY?

These two central parts of the Mass are flanked by two smaller parts: the Introductory Rites and the Concluding Rites. The Introductory Rites open the celebration of the Mass and prepare the faithful for their sacred encounter with God in His Word and in the Eucharist. So if we come in late, we are not “preparing” properly for Mass. After Communion, the Concluding Rites formally close the celebration and send the people forth to do good works and take Christ into the world. Mass is not over at Communion. We must remember to kneel down after receiving the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ and give thanks and praise to Him. Then after the Blessing, we sing joyfully together as the priest processes out.

The

chart below lays out these four main sections of the Mass, which serve

as an umbrella for the smaller, individual parts of the liturgy. Keeping

this "big picture" of the Mass in mind will be helpful to become more

faithful participants.

By Ruben Beltran

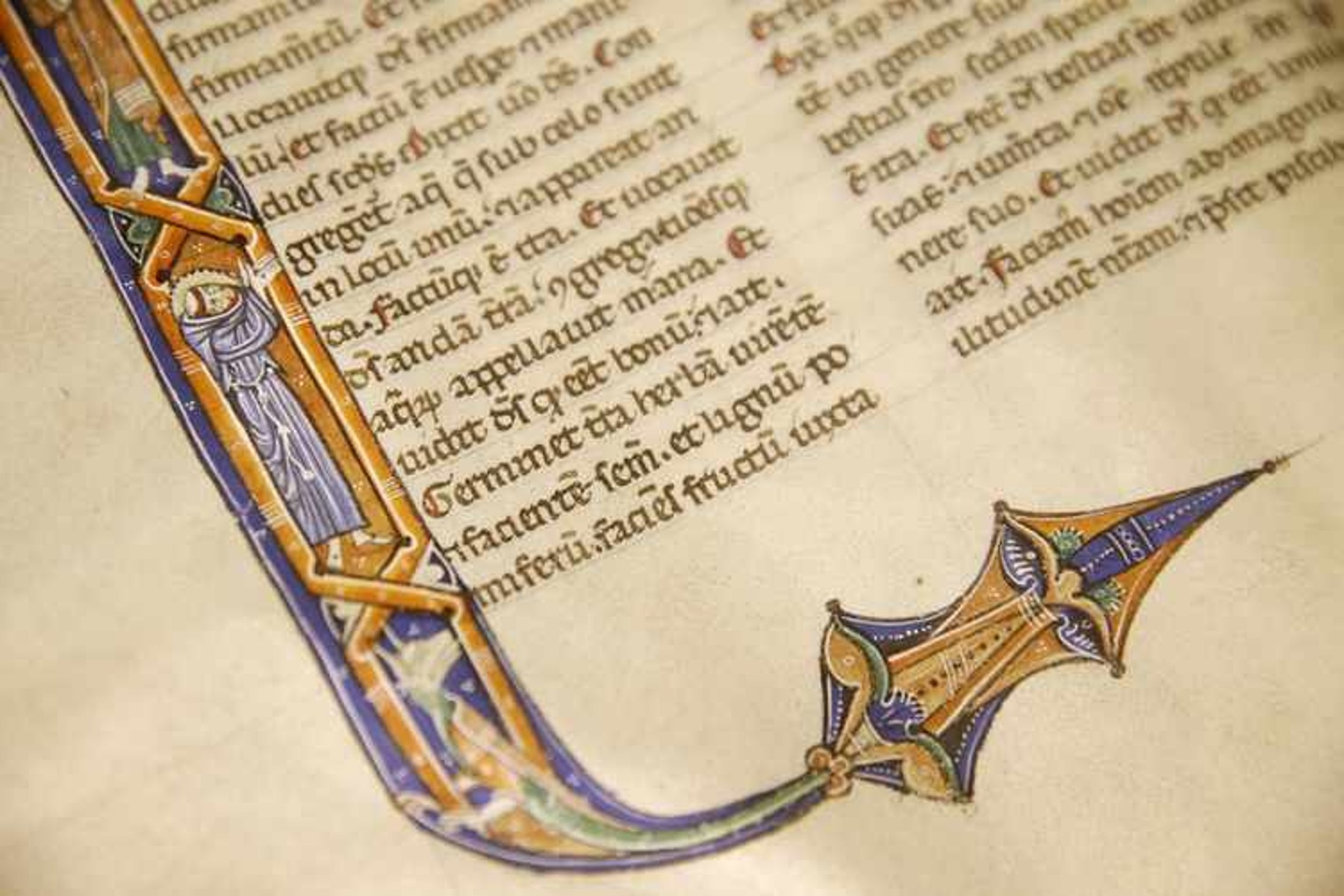

"Where in Scripture Does Jesus Speak of His Body and Blood as Food?" The Eucharist is a sacrament in which is contained—by the marvelous conversion of the whole substance of bread into the Body of Jesus Christ, and that of wine into His precious Blood—truly, really, and substantially, the Body, the Blood, the Soul, and Divinity of the same Lord Jesus Christ, under the appearance of bread and wine, as our spiritual food. The Catechism of the Catholic Church teaches in paragraph 1324: “The Eucharist is ‘the source and summit of the Christian life.’ The other sacraments, and indeed all ecclesiastical ministries and works of the apostolate, are bound up with the Eucharist and are oriented toward it. For in the blessed Eucharist is contained the whole spiritual good of the Church, namely Christ Himself, our Pasch."

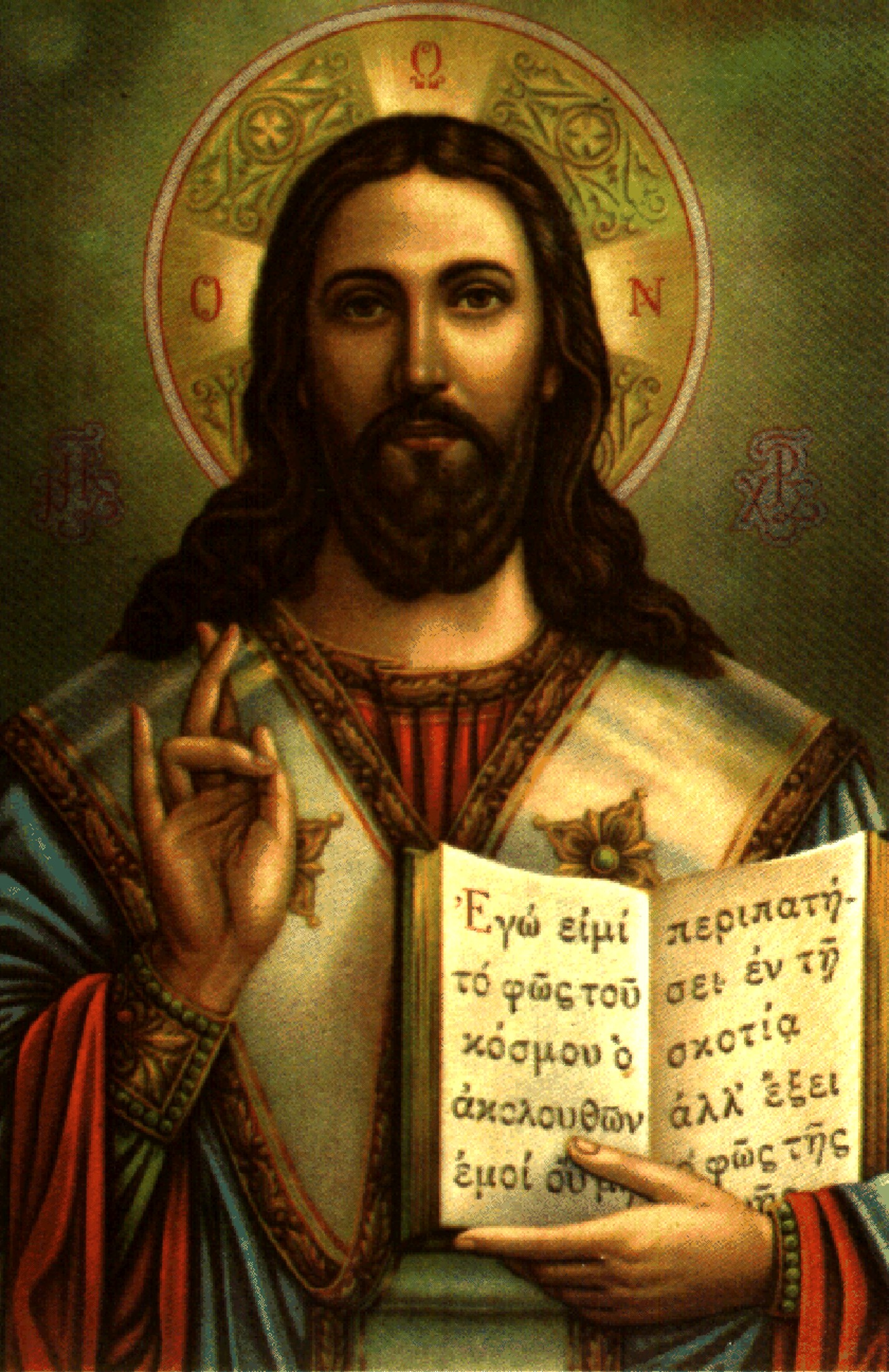

But where in the Bible does Jesus explicitly say that He will give us His flesh to eat?

We are all familiar with the institution narratives in the Gospels, specifically Luke’s Gospel, because we hear it every week at Mass. It is the first place most Catholics will turn to show that Jesus Instituted the Eucharist: “And He took bread, and when He had given thanks, He broke it and gave it to them, saying, ‘This is my body which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me’” (Luke 22:19). However, the Sixth Chapter of the Gospel of John (one which every Catholic should read and be familiar with) gives us the “Bread of Life Discourse”. This Chapter is one of the most important sermons Jesus ever preached but also one of the most disastrous from a human perspective.

Beginning

in verse 35, we see Jesus calling Himself the “Bread of Life” and

saying that we must eat His flesh and drink His blood—something which is

forbidden in the book of Leviticus (17:10). The Jews who are listening

are scandalized by this and begin to murmur: "Then many of His disciples who were listening said, “This saying is hard; who can accept it?... As a result of this, many of His disciples returned to their former way of life and no longer accompanied Him."

What is interesting is that Jesus, knowing that those listening to Him are disturbed by His words, never backpedals. Instead, Jesus intensifies what He says. In the original Greek (John 6:49, 50, 51, 53), Jesus made use of a more common verb for eating, "esthio". However, beginning in verse 54, after the Jews dispute among themselves, Jesus changes the word to "trogo," which means to “chew” or to “gnaw” like an animal. Jesus, knowing in Himself that His disciples murmured at it, said to them, "Do you take offense at this? Then what if you were to see the Son of Man ascending where He was before? It is the Spirit that gives life, the flesh is of no avail; the words that I have spoken to you are Spirit and Life.” Here Jesus explains how this will all take place: “It is the Spirit that gives life...”; so they must wait until the Spirit is given, the Spirit that raises the Body of Christ from the dead. It will be the Holy Spirit that makes Christ’s flesh and blood holy, glorious, and powerful, as food for our souls and bodies.

In verse 66, many of Christ’s disciples leave. Jesus never tries to stop them; in fact, Jesus turns to the Apostles and asks if they, too, wish to leave. In every other instance, when the disciples find something hard to understand, Jesus is quick to explain what He was trying to say, but here we find Jesus allowing words to remain “scandalous”—even for the Twelve. If Jesus was speaking figuratively, He would have taken the time to make that clear to His disciples, but He doesn’t. He was willing to allow the Twelve to leave rather than to soften or change what He said.

Jesus said what He meant, and meant what He said: “My flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed.”

Published in the Bulletin of February 15, 2015

By Jimmy Akin

"Why Was Jesus Tested for Forty Days in the Desert?" The Gospel for the First Sunday of Lent in 2015 commemorates Jesus’ forty days of testing in the desert. Jesus decided to spend forty days of testing in the desert as preparation for His adult ministry (forty days is the traditional number for spiritual testing). The reason He chose to begin His ministry with a time of testing was to (a) set an example for us, (b) reveal His identity as Son of God to the opposing supernatural forces, and (c) reveal the nature of His ministry as Messiah to us.

Here is how the Catechism of the Catholic Church(CCC) explains the event (538): The Gospels speak of a time of solitude for Jesus in the desert immediately after His baptism by John. Driven by the Spirit into the desert, Jesus remained there for forty days without eating; He lived among wild beasts, and angels ministered to Him [cf. Mk 1:12-13]. At the end of this time Satan tempted Him three times, seeking to compromise His filial attitude toward God. Jesus rebuffed these attacks, which recapitulated the temptations of Adam in Paradise and of Israel in the desert, causing the devil to leave Him “until an opportune time” [Lk 4:13].

The Catechism continues (539): The evangelists indicated the salvific meaning of this mysterious event: Jesus is the new Adam who remained faithful, unlike the first Adam who gave in to temptation. Jesus fulfilled Israel’s vocation perfectly: in contrast to those who had once provoked God during their forty years in the desert, Christ revealed Himself as God’s Servant, totally obedient to the divine will. In this, Jesus is the devil’s conqueror: He “binds the strong man” to take back his plunder (cf. Ps 95:10; Mk 3:27). Jesus’ victory over the tempter in the desert anticipates victory at the Passion—the supreme act of obedience of His filial love for the Father.

The CCC(540) says that Jesus’ temptation reveals the way in which the Son of God is Messiah, contrary to the way Satan proposed to Him and the way men wish to attribute to Him (cf Mt 16:2 1-23). This is why Christ vanquished the Tempter for us: “For we have not a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but one who in every respect has been tested as we are, yet without sinning” (Heb. 4:15). By the solemn forty days of Lent, the Church unites herself each year to the mystery of Jesus in the desert.

CCC 566: The temptation in the desert shows Jesus, the humble Messiah, who triumphs over Satan by His total adherence to the plan of salvation willed by the Father. One additional thing that should be known is that the biblical term for “tempting” is the same as the term for “testing.” Jesus was not tempted in the sense that we are—that is, having evil desires—but in the sense of being tested to see if it was possible to tempt Him in the sense of giving Him evil desires. He was not capable of receiving such desires because of His infinite holiness as Son of God.

Published in the Bulletin of February 22, 2015

by Ruben Beltran

"Why Does the Church Encourage the Faithful to Practice Fasting, Almsgiving, and Prayer--Especially at Lent?"

In order to answer this question, we need to go all the way back to

our first parents—all the way back to the Garden of Eden. If you ask

your average Catholic, “What was the reason for the fall?,” the standard

answer will be “pride”. That answer is correct; however, it is

incomplete. A careful reading of Genesis 3:1-6, wherein Eve is tempted

to eat the fruit from the Tree of Knowledge, will reveal three reasons

for the fall: 1) “She saw that it was good for food”; 2) that it was “a

delight to the eyes”; and 3) that it was “desirable to make one wise.”

In these three reasons lies the seed of every sin that has come into the world. The ancient Jewish Rabbis referred to these three reasons as the “threefold lust.” St. John refers to the threefold lust as the “lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life” (1 John 2:16). In more modern terms, these three reasons have come to be known as “Money, Sex, and Power.” Let us see some of the things to which each refers:

- Lust of the Flesh: This refers to a disordered desire for pleasure (food, drink, alcohol, sex, drugs, etc.)

- Lust of the Eyes: This refers to a disordered desire for possessions (money, clothing, cars, houses, investments, gambling, etc.)

- Pride of Life: This refers to pride/power (being selfish, egotistical, controlling, and prone to anger, etc.)

These three desires drive the world; however, they are not in themselves inherently evil. It is only when we put these desires before God that they become disordered, when we choose the least good over the greatest Good—which is God. It is the fact that we want these things on our own terms without God which gives them their lustful nature.

So what is a good Catholic to do? Well, onto the scene steps Jesus, the “New Adam” who reverses Adam and Eve’s sin in the garden and shows us how to conquer sin at its root. One of the first things Jesus does is head out to the desert (Lk 4:1-13). In this context, the desert symbolizes what became of Paradise; that is, Adam turned it into a barren desert by allowing sin to enter the world. Satan proceeds to try and tempt Christ with the threefold lusts: Food (flesh), Kingdom (possessions), and Manifestation of Power (pride). Jesus uses Scripture (specifically the book of Deuteronomy) to combat Satan, and that is what each of us should do. We should always turn to the Word of God to combat the Evil One.

However, Jesus unites Scripture with fasting, almsgiving, and prayer to conquer Satan. Fasting helps us overcome the lust of the flesh and strengthens our wills so that we realize that we cannot live by bread alone. Almsgiving helps us overcome the lust of the eyes and allows us to detach ourselves from the things of the world and to realize that we are to worship God alone. Finally, Prayer humbles us and takes pride out at its root. It helps us realize that without God we are powerless. Christ gives us all we need to conquer the Evil One and reverse the fall of Adam and Eve. This Lent let us use these weapons that Our Lord has given us in order to become more like Him.

Published in the Bulletin of March 1, 2015

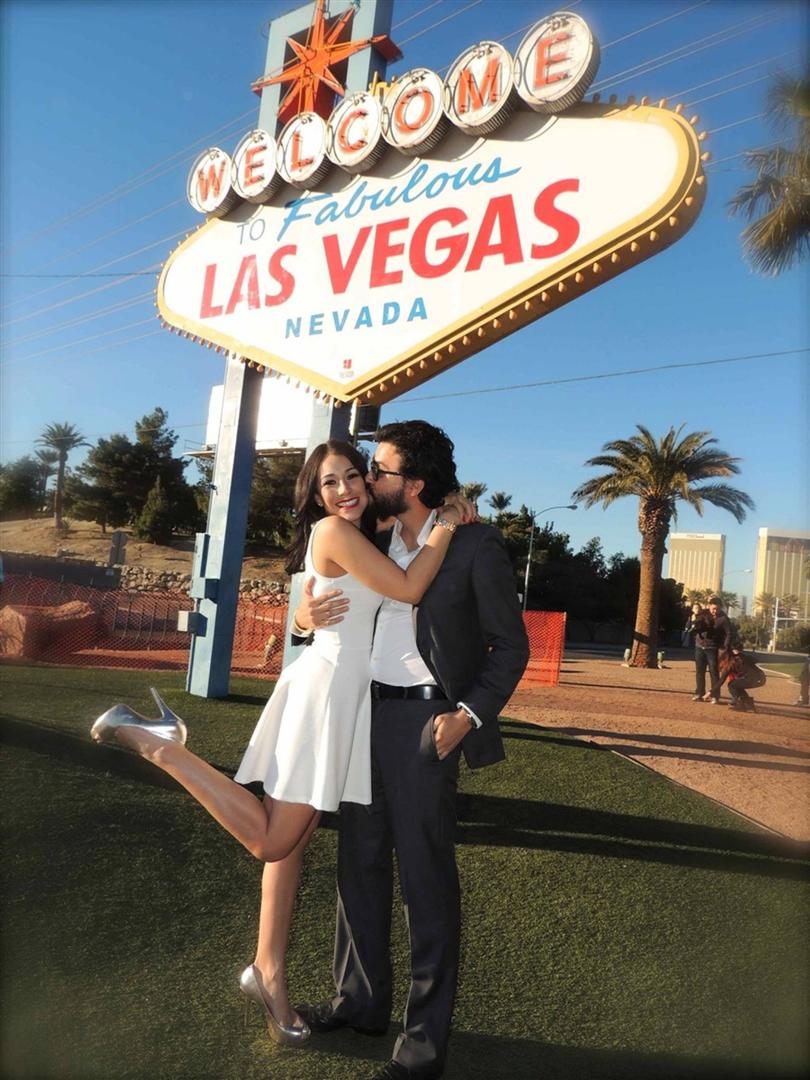

Submitted by Deacon Joe & Lorraine Mizerski (Parish Annulment Facilitators)

"What is a Catholic Annulment?" "Annulment"is

an unfortunate word that is sometimes used to refer to a Catholic

"declaration of nullity." Actually, nothing is made null through the

process. Rather, a Church tribunal (a Catholic Church court) declares

that a marriage thought to be valid according to Church law actually

fell short of at least one of the essential elements required for a

binding union.

A valid Catholic marriage results from five elements: (1) the spouses are free to marry; (2) they freely exchange their consent; (3) in consenting to marry, they have the intention to marry for life, to be faithful to one another and be open to children; (4) they intend the good of each other; and (5) their consent is given in the presence of two witnesses and before a properly authorized Church minister. Exceptions to the last requirement must be approved by church authority.

Why does the Church require a divorced Catholic to obtain a declaration of nullity before re-marrying in the Church? The Church presumes that marriages are valid and lifelong; therefore, unless the ex-spouse has died, the Church requires the divorced Catholic to obtain a declaration of nullity before re-marrying. The tribunal process seeks to determine if something essential was missing from the relationship from the moment of consent, that is, the time of the wedding. If so, the Church can declare that a valid marriage never actually brought occurred on the wedding day.

What does the tribunal process involve? Several steps are involved. The person who is asking for the declaration of nullity (the petitioner) submits written testimony about the marriage and a list of persons who are familiar with the marriage. These people must be willing to answer questions about the spouses and the marriage. The tribunal will contact the ex-spouse (the respondent), who has a right to be involved. The respondent's cooperation is welcome but not essential. In some cases the respondent does not wish to become involved; the case can still move forward. Both the petitioner and the respondent can read the testimony submitted, except that protected by civil law (for example, counseling records). Each party may appoint a Church advocate who could represent the person before the tribunal. A representative for the Church, called the defender of the bond, argues for the validity of the marriage. After the tribunal has reached a decision, it is reviewed by a second tribunal. Both parties can participate in this second review as well.

How long does the process take? It can vary from diocese to diocese, often taking 12 to 18 months or longer in some cases. The diocesan tribunal may be able to give you a more exact estimate.

How can a couple married for many years present a case? The tribunal process examines the events leading up to, and at the time of, the wedding ceremony, in an effort to determine whether what was required for a valid marriage was ever brought about. The length of common life is not proof of validity but a long marriage does provide evidence that a couple had some capacity for a life-long commitment. It does not prove or disprove the existence of a valid marriage bond.

If a marriage is declared null, does it mean that the marriage never existed? No. It means it was not valid according to Church law. A declaration of nullity does not deny that a relationship existed. It simply states that the relationship was missing something that the Church requires for a sacramental marriage.

If a marriage is annulled, are the children considered illegitimate? No. A declaration of nullity has no effect on the legitimacy of children, since the child's mother and father were presumed to be married at the time that the child was born. Legitimacy depends on civil law.

Since I do not plan to re-marry, why should I present a marriage case? Some people find that simply writing out their testimony helps them to understand what went wrong and why. They gain insights into themselves. Others say that the process allowed them to tell their whole story for the first time to someone who was willing to listen. Many find that the process helped them to let go of their former relationship, heal their hurts, and move on with their lives. A person cannot know today if they might want to marry in the future when crucial witnesses may be deceased or their own memories may have dimmed.

Why does the Catholic Church require an intended spouse, who is divorced but not Catholic, to obtain an annulment before marrying in the Catholic Church? The Catholic Church respects all marriages and presumes that they are valid. Thus, for example, it considers the marriages of two Protestant, Jewish, or even nonbelieving persons to be binding for life. The Church requires a declaration of nullity to establish that an essential element was missing in that previous union preventing it from being a valid marriage. This is often a difficult and emotional issue. If the intended spouse comes from a faith tradition that accepts divorce and remarriage, it may be hard for them to understand why they must go through the Catholic tribunal process. Couples in this situation may find it helpful to talk with a priest or deacon. To go through the process can be a sign of great love of the non-Catholic for their intended spouse.

My fiancé and I want to marry in the Catholic Church. He has been married before and has applied for an annulment. When can we set a date for our wedding? You should not set a date until the annulment has been finalized. First, his petition may not be granted. Second, even if the petition is eventually granted, there may be unexpected delays in the process. Many pastors will not allow the couple to set a date until the petition is officially approved.

To begin your own annulment process, please contact the Parish Annulment Facilitators, Deacon Joe & Lorraine Mizerski, at (626) 282-2744, ext. 333.

Published in the Bulletins of March 8 and March 15, 2015

By Scott Hahn

"What is the Anointing of the Sick?" When Jesus commissioned the Twelve, they went out into the world and saw immediate results. In St. Mark’s Gospel we learn that they “anointed with oil many who were sick and healed them” (Mk 6:13). They must have been astonished at the power flowing through them. Yet it was a mere shadow of the task that still lay ahead of them. For, as Jesus made clear elsewhere in St. Mark’s Gospel, it is a greater work to forgive sins than to heal even the gravely ill. (Mk 2:9).

Jesus healed people with dire illnesses and disabilities as a sign of spiritual healing: “…that you may know that the Son of Man has authority on earth to forgive sin” (Mk 2:10). The physical signs were there for the sake of a spiritual reality. They were a concession to human weakness. In fact, after the apostles had witnessed many such marvels, Jesus assured them that they would accomplish “greater works than these” (Jn 14:12).

In the beginning of their ministry, the apostles, like Jesus, restored bodily health. But it was a sign of the deeper healing they would accomplish, through the Church, after Pentecost. We catch a glimpse of the Church’s ministry of spiritual healing in the Letter of St. James: “Is any among you sick? Let him call for the elders [presbyters, or priests] of the Church, and let them pray over him, anointing him with oil in the name of the Lord; and the prayer of faith will save the sick man, and the Lord will raise him up; and if he has committed sins, he will be forgiven” (Jas 5:14-15). This is the Sacrament we know today as the Anointing of the Sick. But it’s fair for us to ask today why physical illness should be an occasion for spiritual healing. There are many good reasons, not least that grave physical suffering is often accompanied by difficult spiritual trial. When we are in extremis, we are far more likely to be tempted to doubt God’s goodness and power—or even His existence. Job’s wife sincerely expected her husband to give in to despair and “curse God” (Job 2:9).

Sacramental oil gives us the grace we need to face such trials. Consider what the symbol of oil suggested to the early Christians. Oil healed, and oil strengthened. It was a base for many medicines. It was also a liniment used by athletes in the arena. Olive oil was a rub down that strengthened wrestlers for a contest and enabled them to slip away from the grip of their enemies. For Christians, all of these worldly values are symbolic of the spiritual value of anointing. Anointing both heals and strengthens us spiritually, and enables us to slip away from the devil’s grasp and endure our contest with him—and, more than endure, to prevail, to be “more than conquerors through Him who loved us” (Rom 8:37). The anointing even brings about that great marvel that Jesus alluded to in St. Mark’s Gospel: the forgiveness of sins. Thus we can face even certain death with a serene and peaceful conscience, in the reasonable hope that death will be our gateway to eternal life.

Sometimes, the sacramental anointing will bring about physical healing as well, if healing will be conductive to the salvation of the soul. That’s wonderful but unusual; and actually, it’s far less a marvel than the Sacrament’s ordinary effects. Anointing is far more likely to give us what we really need: humble acceptance of our suffering, in union with the suffering of Christ and in atonement for sins, especially our own. Anointing helps us transform physical suffering into something more deeply remedial, something truly redemptive.

(Published in the Bulletin of March 22, 2015)

From the Website of Catholic News Agency

So they took branches of palm trees and went out to meet Him, crying, "Hosanna!

Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord, even the King of Israel!

And Jesus found a young ass and sat upon it; as it is written, "Fear not,

daughter of Zion; behold, your king is coming, sitting on the colt of an ass” (Jn 12:13-15).

The Palm Sunday procession is formed of Christians who, in the "fullness of faith," make their own the gesture of the Jews and endow it with its full significance. Following the Jews' example, we proclaim Christ as Victor: “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is He who comes in the Name of the Lord.” But by our faith we know, as they did not, all that His triumph stands for. He is the Messiah, the Son of God. He is the sign of contradiction, acclaimed by some and reviled by others. Sent into this world to take us from sin and the power of Satan, He underwent His Passion, the punishment for our sins, but comes forth triumphant from the tomb, the victor over death, making our peace with God and taking us with Him into the kingdom of His Father in heaven. (For further reading go to: CatholicCulture.org.)

HOLY THURSDAY – THE BEGINNING OF THE HOLY TRIDUUM: Except for the celebration of the Easter Vigil, Holy Thursday is possibly one of the most important, complex, and profound days of celebration in the Catholic Church. Holy Thursday celebrates the institution of the Eucharist as the true Body and Blood of Jesus Christ and the institution of the Sacrament of the Priesthood. During the Last Supper, Jesus offers Himself as the Passover sacrifice, the sacrificial lamb, and teaches that every ordained priest is to follow the same sacrifice in the exact same way. Christ also bids farewell to His followers and prophesizes that one of them will betray Him and hand Him over to the Roman soldiers, and that one would deny Him three times.

During the night, after sundown—because Passover begins at sundown—the Holy Thursday Liturgy takes place, marking the end of Lent and the beginning of the Sacred "Triduum,” (three days) of Holy Week. These days are the three holiest days in the Catholic Church. This Mass stresses the importance Jesus puts on the humility of service, and the need for cleansing with water, a symbol of baptism. Also emphasized are the critical importance of the Eucharist and the sacrifice of Christ’s Body, which we now find present in the consecrated Host.

At the conclusion of the Mass, the faithful are invited to continue Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament, just as the disciples were invited to stay up with the Lord during His agony in the garden before His betrayal by Judas. After Holy Thursday, no Mass will be celebrated again in the Church until the Easter Vigil celebrates and proclaims the Resurrection of the Lord Jesus Christ.

GOOD FRIDAY: On Good Friday, the entire Church fixes her gaze on the Cross at Calvary. Each member of the Church tries to understand at what cost Christ has won our redemption. In the solemn ceremonies of Good Friday, in the Adoration of the Cross, in the chanting of the 'Reproaches', in the reading of the Passion, and in receiving the pre-consecrated Host, we unite ourselves to our Savior, and we contemplate our own death to sin in the Death of our Lord.

The Church--stripped of its ornaments, the altar bare, and with the door of the empty tabernacle standing open--is as if in mourning. In the fourth century the Apostolic Constitutions described this day as a "day of mourning, not a day of festive joy," and it was called the "Pasch (passage) of the Crucifixion." The liturgical observance of this day of Christ's suffering, crucifixion and death evidently has been in existence from the earliest days of the Church. No Mass is celebrated on this day, but the service of Good Friday is called the Mass of the Presanctified because Communion (in the species of bread), which had already been consecrated on Holy Thursday, is given to the people.

Traditionally, the organ is silent from Holy Thursday until the Alleluia at the Easter Vigil, as are all bells or other instruments, the only music during this period being unaccompanied chant. The omission of the prayer of consecration deepens our sense of loss because Mass throughout the year reminds us of the Lord's triumph over death, the source of our joy and blessing. The desolate quality of the rites of this day reminds us of Christ's humiliation and suffering during his Passion. We can see that the parts of the Good Friday service correspond to the divisions of Mass:

- Liturgy of the Word - reading of the Passion.

- Intercessory prayers for the Church and the entire world, Christian and non-Christian.

- Veneration of the Cross

- Communion, or the 'Mass of the Pre-Sanctified.'

HOLY SATURDAY: On Holy Saturday the Church waits at the Lord's tomb, meditating on his suffering and death. The altar is left bare, and the sacrifice of the Mass is not celebrated. Only after the solemn vigil during the night, held in anticipation of the resurrection, does the Easter celebration begin, with a spirit of joy that overflows into the following period of fifty days. The the Easter Vigil is the most beautiful liturgy in the Church—and the liturgy that marks the beginning of Easter. We are awaiting our Master's return with our lamps full and burning, so that He will find us awake and will seat us at His table The vigil is divided into four parts:

- Service of Light

- Liturgy of the Word

- Liturgy of Baptism

- Liturgy of the Eucharist

From its very beginnings, the Christian community placed the celebration of Baptism within the context of the Easter Vigil. On this night, catechumens will be baptized, and the congregation will renew their Baptismal promises.

(Published in the Bulletin of March 29, 2015)

By Saint Mary’s Press - Living in Christ Series

"How Do We Participate in the Paschal Mystery?" Individual Christians participate in the Paschal Mystery through their own sacrifices and through the sacramental life of the Church.

The Paschal Mystery is not just about our own salvation; it calls us to continue Christ’s mission, inviting other people to know God’s saving power.

Consider the Ascension, the final event in the Paschal Mystery definition. Christ’s Ascension marks the beginning of the mission of the Church. At His Ascension, Christ gives the Apostles their mission: “Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, until the end of the age” (Matthew 28:19–20). Soon after this, the Apostles receive the fullness of the Holy Spirit, empowering them for this mission.

Christ Himself set the foundation for uniting our sacrifices with His for the sake of our salvation and for the salvation of others. He instructs His disciples, “Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me. For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (Matthew 16:24–25). After we have been redeemed through our Baptism, we want to share the Gospel with others, even though doing so often requires some form of sacrifice. We might need to sacrifice comfort, popularity, or personal freedom. Or our sacrifice might be the pain of being rejected, misunderstood, or even tortured for speaking the truth and acting on it. The Church holds martyrs as exemplars of the Paschal Mystery because of the high price they paid in following Christ. We endure these sacrifices not on our own power, but by seeing them as extensions of Christ’s Passion. In prayer we consciously unite our sacrifices—even the suffering we do not choose, such as the suffering caused by illness or accidents—with Christ’s Passion and death.

There is a fine distinction to be made here. Taking up our cross does not mean that we earn our own salvation; that work is Christ’s alone. However, our willingness to endure suffering and even death to continue Christ’s mission earns us merit in the sight of God. We avoid egoism and give God His rightful glory by remembering that we can take up our cross only because God first reaches out to us and gives us the needed strength to do so. The sacramental life of the Church is the superlative source for experiencing God’s saving power and receiving the grace necessary to continue Christ’s mission. In the Sacrament of Baptism we are redeemed from our slavery to sin, and our original justice is restored. In the Sacrament of Confirmation we receive the fullness of the Holy Spirit to continue Christ’s saving mission. In the Sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation, we are again freed from slavery to sin when sin reenters our lives. In the Sacraments of Matrimony and Holy Orders, we receive the graces needed to continue Christ’s mission of salvation in family life or as an ordained minister of the Church. And in the Sacrament of Anointing of the Sick, we receive God’s healing power and the grace to unite our suffering with Christ’s Passion.

The Sacrament of the Eucharist has a special place in our participation in the Paschal Mystery. In the Eucharist we receive Christ’s Body and Blood, the same Body and Blood that was broken and poured out to redeem us. We receive the same Christ who was raised as the promise of our own eternal life with God. Our hearing of the Word of God and our reception of the Eucharist is both the sign and the reality of our full communion with God. The Eucharist makes Christ’s Paschal Sacrifice present to us, so that we truly and actively participate in its saving power.

(Published in the Bulletin of April 19, 2015)

By Ruben Beltran

"What is Catholic Education?" The Second Vatican Council’s Gravissimum Educationis

(Declaration on Christian Education) insists that “a true education

aims at the formation of the human person in the pursuit of his ultimate

end and of the good of the societies of which he is a member and in

whose obligations as an adult he will share.” The same document speaks

of helping young people “to develop harmoniously their physical, moral,

and intellectual endowments,” and it insists they get it.

The Vatican’s Congregation for Catholic Education defines a school as “a place of integral formation by means of a systematic and critical assimilation of culture.” Integral means all the pieces are there and they fit together. Formation means education concerns the kind of person one becomes, not just what one knows. In other words, it concerns intellectual and moral knowledge but also virtues—habits of acting for the true, the good, and the beautiful. Integral formation also includes spiritual formation. The integral formation of the human person, which is the purpose of education, includes the development of all the human faculties of the students, together with preparation for professional life, formation of ethical and social awareness, and religious education.”

In short, this document speaks of liberal education; that is, the education of the “free man,” the person who knows his mind and exercises virtue; someone who seeks the true, the good, and the beautiful in his own pursuit of happiness and in his contribution to that of others. The Church presupposes all of that when she speaks of Catholic or Christian education.

The proper function of Catholic education involves evangelization and discipleship training for life. As the "Declaration on Catholic Education" states: “A Christian education…has as its principal purpose this goal: that the baptized become ever more aware of the gift of faith they have received and that they learn how to worship God, especially in liturgical action, and be conformed in their personal lives. Also, that they develop in the fullness of Christ and strive for the growth of the Mystical Body; that they are aware of their calling and learn not only how to bear witness to the hope that is in them, but also how to help in the Christian formation of the world.”

Notice that the principal purpose of Catholic education is to form disciples—people who know and follow Christ and make Him known. Not excellence in education, as important as that is; not equipping students to have successful careers, however valuable that may be. But forming disciples. Do our students know Jesus, follow Him and share Him with others? In our zeal for academic excellence, do we obscure or minimize the evangelical purpose of our schools? How many leaders of Catholic schools can honestly say their institutions are principally about forming educated disciples? The “education part” of Catholic education must keep the “Catholic part” honest when it comes to the formation of the whole person, including the intellectual dimension. This helps Catholic education avoid becoming a glorified Bible study or apologetics program. When that happens, the “Catholic part” of Catholic education suffers, too. Vital dimensions of the student’s life are not fully developed in light of the Gospel because they’re not developed or adequately developed. The minds and wills God gave young people to exercise and grow are stunted.

But the “Catholic part” of Catholic education must keep the “education part” honest, too. Otherwise, Catholic schools may achieve academic excellence but at the expense of forming disciples. Ironically, such education is less than full academic excellence, for it has shaped the student without regard for his ultimate end—union with God. Catholic education must form the whole person according to intellectual, moral and physical excellence. But all of that must be ordered to the formation of genuine disciples of Jesus—people who know Him, love Him and serve Him.

That’s what makes Catholic Education Catholic.

(Published in the Bulletin of April 26, 2015)

WHAT IS THE CLASSICAL APPROACH TO EDUCATION?

“Creating the ability to think is our goal in a classical curriculum; we want our children to acquire the art of learning. It is not the number of facts they are acquainted with that measure the educational success, but what they are able to do with the facts: whether they are able to make distinctions, to follow an argument, to make reasonable deductions from the facts, and finally, to have the right judgment about the way things are.” — Laura Berquist (Designing Your Own Classical Curriculum)

A Classical Education:

· Teaches the Child How to Think

· Follows the Child's Natural Stages of Learning

· Takes Account of the Child's Individual Needs

· Supports the Spiritual Formation of the Child

· Allows the Parents to Play an Integral Role

A Classical Education Creates:

· Learners who have the knowledge and ability to perform independent research.

· Students who are effective Communicators

· Students who are able to read and comprehend diverse written materials.

· Students who demonstrate rhetorical and analytical skills in their written work.

· Students who express themselves with confidence in written communication.

· Students who are independent thinkers

· Students who are able to analyze information, and form and explain their own opinions

A classical education will give our children the beginning of the education every educated person in Western Civilization once received, a classical or liberal arts education. The idea is to educate the students so that they develops all the powers of their souls, and their minds are formed, strengthened, and developed. The end of this educational process is wisdom. Man desires by nature to know, and that means we want to have not only the facts, but the reasons for the facts. We want to think about the most noble things, the most interesting in themselves. Therefore, the goal of education is to teach children how to think; to help them learn the art of learning. If children learn how to learn, they will be to master any subject. Thinking can be done well or badly, but one can be taught to do it well. In large measure, the role of the teacher of grade and high school children is this: teaching children to think well. It begins in wonder and aims at wisdom.

The tools of learning, through which children learn the art of learning, are acquired by concentrating, at each stage of intellectual formation, on the areas of development that are appropriate to that stage in the child’s intellectual and spiritual development. Further, all we do will be faithful to the doctrine and teaching of the Catholic Church, which shall enlighten and inform all the areas of the curriculum.

(Published in the Bulletin of April 26, 2015)

By Michael Trueman

He was confronted by the religious leaders of the day, who knew divorce was wrong, though made legal in the Jewish and Roman societies. When asked if divorce was okay, our Lord responded: “Have you not read that the one who made them at the beginning ‘made them male and female,’ and said, ‘For this reason a man shall leave his father and mother and be joined to his wife, and the two shall become one flesh’? So they are no longer two, but one flesh. Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate” (Mt 19:4b–6).

“The married couple forms ‘the intimate partnership of life and love established by the Creator and governed by his laws; it is rooted in the conjugal covenant, that is, in their irrevocable personal consent.’ Both give themselves definitively and totally to one another. They are no longer two; from now on they form one flesh. The covenant they freely contracted imposes on the spouses the obligation to preserve it as unique and indissoluble” (Catechism of the Catholic Church [“CCC”] 2364).

Jesus brought the discussion back to the origin of God’s creation of man and woman. God designed men and women for marriage, to be one flesh in sexual cooperation to bring about the wonder of children and the mutual self-giving of the spouses to each other for the entirety of their earthly lives together. You might say that Jesus was only teaching Christians—and that the Church’s consistent teaching through the centuries on the indissolubility of marriage is only for Christians—but this is not true. Jesus, in citing God’s creation of men and women, applied this teaching to all of humanity, regardless of religion or nationality.

The Church presumes, therefore, that all “first time for both” marriages—including the marriages of Catholics, other Christians, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, etc—create a covenant for the husband and wife’s entire life. Therefore, if you were married, chances are you are bound by a covenant of marriage with that person.

Marriage is an Indissoluble Covenant God’s teaching holds that marriage is a covenant that cannot be revoked or ended by human decision or human law. This is what we mean by marriage being indissoluble. When a man and woman enter marriage for the first time, the bond of marriage is presumed to endure until the death of one of the parties; but this presumption can be overturned, as will soon be explained.

The Vows Bring about a Marriage Establishing a covenant of marriage is relatively simple—a man and woman who are not already in a marriage covenant need only to exchange their consent (i.e., the wedding vows) publicly before witnesses. “The marriage consent is an act of the will which signifies and involves a mutual giving which unites the spouses between themselves and at the same time binds them to the children which they may eventually have, with whom they constitute one family, one single home, a ‘domestic Church’” (Blessed John Paul II, “Consent Makes Marriage, Its Defense by the Church,” 28 January 1982, no. 4, quoted in William H. Woestman (ed.), Papal Allocutions to the Roman Rota: 1939–1994 (Ottawa: Faculty of Canon Law, Saint Paul University, 1994), p. 172). There are, of course, several requirements to wed, such as proper age and not being forced into marriage, but the basic requirement is the exchanging of the wedding vows. With Catholics, however, there is one other essential requirement: the couple must express their vows before a priest or deacon of the Catholic Church.

Married “Outside the Church” You’ve heard it said, “I married outside the Church.” This means that a Catholic did not marry in front of a priest or deacon and two witnesses. The union may be recognized by the State government or even by a non-Catholic denomination or different religion, but it is not recognized as a marriage covenant by the Church. If the man and woman are in such a union, they may correct what was previously missing and exchange their consent before a priest or deacon and two witnesses. This is called a convalidation ceremony, which is in every way the wedding ceremony that all Catholics experience. However, if one or the other is in a marriage covenant, then he or she will need to be freed from that marriage covenant before being able to celebrate a marriage recognized by the Church through the convalidation ceremony.

Marriage, Separation, and Divorce … and Remarriage For someone in a marriage covenant who has separated and has obtained a civil divorce, there is no serious offense with their situation provided they live a life of chastity, respecting the covenant of marriage. For the divorced Catholic, this means he or she can continue in the practice of their Catholic faith by reception of the sacraments (except marriage), by taking on certain parish-based ministries, etc. However, someone in a marriage covenant who has separated, obtained a civil divorce, and has entered a new union (i.e., civil marriage) or is not living chastely is violating the covenant of his or her first marriage. This way of life is at odds with God’s design for him or her, and for the covenant of marriage. For Catholics in the new union, this means they must refrain from receiving the sacraments.

I am “Remarried” without an Annulment — What Do I Do? If the covenant of marriage is presumed to exist, the most common way to realize another marriage in the Church is to challenge the validity of the prior marriage or cite where and how divine law permits a prior bond of marriage to be dissolved. Only after it is declared that a prior marriage was invalidly established, or can be dissolved, can a person validly attempt to enter a new marriage.

Challenging the Validity of the First Marriage Covenant Formal Annulment. Since consent (i.e., the wedding vows) brings the marriage into existence, and consent is a human act, you can always make the claim that the consent that was given was defective—that there was a problem when either (or both) people approached the marriage. It can be argued that one or both parties (1) did not intend what must be intended regarding marriage (e.g., left no openness to children), or (2) did not understand the nature of marriage (e.g., honestly thought it was dissoluble), or (3) did not have the capacity to take on what was required of them in marriage (e.g., made the decision recklessly, without due regard for what would be required of them). These cases take about 12–18 months to complete.

Lack of Canonical Form. This only applies to Catholics (and Eastern Orthodox Christians). Catholics must marry before a priest or deacon. If they do not marry in this way, the law directs that these marriages are not valid due to a lack of canonical form. It is called “canonical form” because the formalities for the ceremony are spelled out in canon law. If you are a Catholic and married outside the Church, you can present a lack of form case. This process takes a few months to complete.

Proving an Impediment Existed. Sometimes, a simple and verifiable fact blocks a marriage from being validly established. The impediment must have been present at the moment of the wedding. One common example is what most dioceses call a Ligamen Case. These cases can be processed only when it is your former spouse who was previously married. Only the parties of a marriage have the right to challenge its validity, so using the rationale that a valid marriage creates a bond to the exclusion of all others, your former spouse’s first marriage impeded him or her from establishing a marriage with you. This process takes about a month or two to complete.

Seeking a Dissolution of the First Marriage Covenant

Pauline Privilege. If you and your former spouse were non-baptized people at the time of your wedding and at any time after the wedding you became baptized, you can seek the Pauline Privilege (cf. St. Paul’s 1 Cor 7:10–15) provided that your former spouse does not want baptism and that he or she does not want to restore common life and live peacefully with you. To seek this, you must want a new marriage since at the moment of the exchange of consent your first bond of marriage is dissolved. This process takes only one or two months to complete.

Privilege of the Faith (Petrine Privilege). If you or your former spouse were non-baptized people at the time of your marriage and at least one of you remained not baptized through your years together, you may seek the Petrine Privilege from the Holy Father. The Church has come to see that for the good of one’s Christian faith, as Vicar of Christ, the Pope can invoke Christ’s own divine power to dissolve a marriage that is not between two baptized people. To seek this privilege, you must want to marry, and this proposed relationship is considered in the application to ensure that, in fact, your Christian faith will benefit from the new union. This process takes about one year to complete.

Non-Consummated Marriage. If a couple, after their exchange of consent, do not at any point have sexual intercourse freely chosen and in the natural manner designed for the conception of children, then the marriage has not accomplished its fullness and can be dissolved by the Pope invoking Christ’s own divine power as his Vicar. While non-consummation is rare in our sex-charged society, it does happen. This process takes about a year to complete.

In all of these cases, contact your local parish or diocese, and you will be guided in the right direction.

Who Needs to be Freed from a Covenant of Marriage? Any person bound by a covenant of marriage who is in a second union or wants a second union needs to challenge the validity or seek a dissolution through the Pauline Privilege, Petrine Privilege, or Non-Consummation case. This applies, of course, to Catholics, but also to everyone else since Christ’s teaching is clear: “Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate” (Mt 19:6b). Whenever a non-Catholic who is in a covenant of marriage wants to marry a Catholic who is free to marry, the non-Catholic first must be freed from his or her covenant of marriage.

Once Free to Marry After the Church determines the presumed covenant of marriage is not valid, or that the bond of marriage can be dissolved through Pauline Privilege, Petrine Privilege, or Non-Consummation, then a “new” marriage can be celebrated in and recognized by the Church.

The Church Understands and Cares The clergy and the laity who assist the clergy know that the times in which we live are hostile and ignorant toward the God-given and wonderful covenant of marriage. Most dioceses appropriate significant financial resources to operate marriage tribunals to help people be faithful to Christ’s teaching, and which may provide the possibility of being freed from a marriage covenant to realize a “new” marriage in the Church. The teaching of Christ, “Therefore what God has joined together, let no one separate,” is not an easy one to understand and follow—but pray to your heavenly Father that, on this path that might seem daunting and even impossible, you will have the grace to understand and the courage to follow. Christ’s Church will walk with you.

Mr. Michael Trueman, M.Div., J.C.L., currently serves as Chancellor of the Archdiocese of Detroit and adjunct part-time faculty for Sacred Heart Major Seminary, Detroit. He is the co-author of two question and answer books on church law (Surprised by Canon Law, Volumes 1 and 2,Servant Books, 2004, 2007).

From www.CatholicsComeHome.Org (Submitted and Edited by Denise McMaster-Holguin)

"Are We Saved Through Faith Alone?" Many Protestants believe we are saved by "faith alone" and they say Catholics believe they can “work” their way into Heaven. How do we answer them? First of all, ask them to show you where in the Catechism, the official teaching of the Catholic Church, does it teach that we can “work” our way into Heaven? They can’t, because it doesn’t. The Catholic Church does not now, nor has it ever, taught a doctrine of salvation by works…that we can “work” our way into Heaven.

Second, ask them to show you where in the Bible does it teach that we are saved by “faith alone.” They can’t, because it doesn’t. The only place in all of Scripture where the phrase “faith alone” appears is in James (James 2:24), where it says that we are NOT…justified (or saved) by faith alone. So, one of the two main pillars of Protestantism (the doctrine of salvation by faith alone) not only doesn’t appear in the Bible, but the Bible actually says the exact opposite: That we are NOT saved by faith alone.

Third, ask them that if works have nothing to do with our salvation, then how come every passage in the New Testament that talks about judgment says we will be judged by our works, not by whether or not we have faith alone? We see this in Romans 2, Matthew 15 and 16, 1 Peter, Revelations 20 and 22, 2 Corinthians 5, and many, many more verses.

Fourth, ask them that if we are saved by faith alone, why does 1 Corinthians 13:13 say that love is greater than faith? Shouldn’t it be the other way around?

As Catholics, we believe that we are saved by God’s grace alone. We can do nothing, apart from God’s grace, to receive the free gift of salvation. We also believe, however, that we have to RESPOND to God’s grace. Protestants believe that, too. However, many Protestants believe that the only response necessary is an act of faith; whereas, Catholics believe a response of faith and works is necessary or, as the Bible puts it in Galatians 5:6, “For in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision has any value, but only faith working through love.”

(Published in the Bulletin of May 10, 2015)

By Ruben Beltran

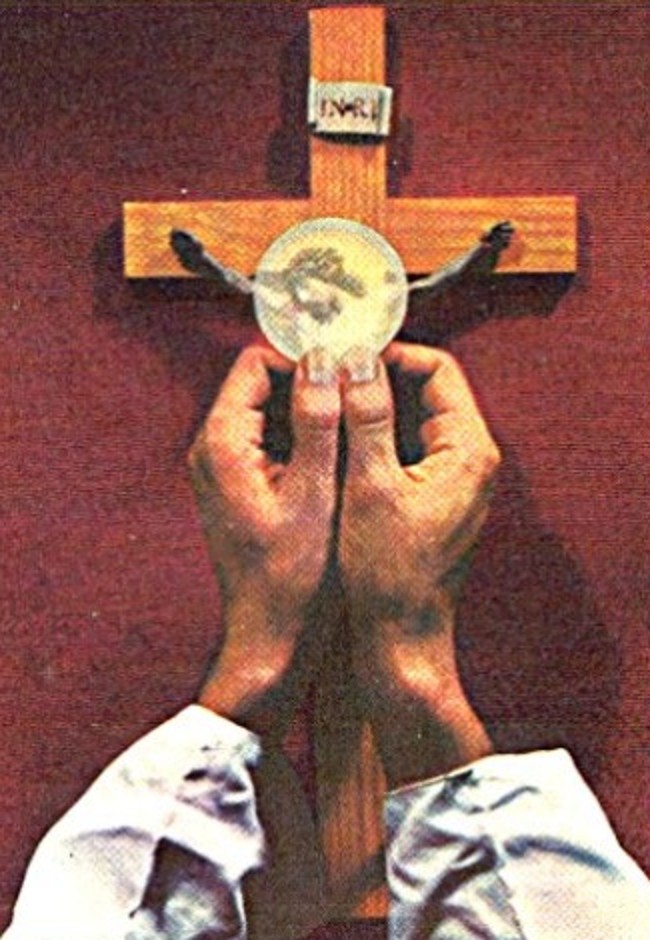

First, let us begin with a person’s spiritual state. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states in paragraph 1385: “To respond to this invitation, we must prepare ourselves for so great and so holy a moment. St. Paul urges us to examine our conscience: ‘Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the Body and Blood of the Lord. Let a man examine himself, and so eat of the bread and drink of the cup. For anyone who eats and drinks without discerning the Body eats and drinks judgment upon himself.’” Anyone conscious of a grave sin must receive the sacrament of Reconciliation before coming to communion.

Also in Paragraph 1457 the Catechism states: “According to the Church’s command, ‘after having attained the age of discretion, each of the faithful is bound by an obligation to faithfully confess serious sins at least once a year.’ Anyone who is aware of having committed a mortal sin must not receive Holy Communion, even if he experiences deep contrition, without having first received sacramental absolution, unless he has a grave reason for receiving Communion and there is no possibility of going to confession.”

Let us now consider appropriate ways to physically receive our Lord. The U.S. Bishops determined that the faithful should bow before receiving Holy Communion as an act of reverence—preferably at the time the person immediately in front is receiving. The norm in the United States is that Holy Communion is to be received standing. However, if an individual person wishes to receive Communion while kneeling, it is perfectly licit for them to do so, and the priest should not hinder them unless there is good reason. The Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments states: “Hence, any baptized Catholic who is not prevented by law must be admitted to Holy Communion. Therefore, it is not licit to deny Holy Communion to any of Christ’s faithful solely on the grounds, for example, that the person wishes to receive the Eucharist kneeling or standing.

Furthermore, to the question of whether it is more appropriate to receive on the tongue or in the hand, the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments goes on to say, “Although each of the faithful always has the right to receive Holy Communion on the tongue, at his choice, if any communicant should wish to receive the Sacrament in the hand, in areas where the Bishops’ Conference with the recognition of the Apostolic See has given permission, the sacred host is to be administered to him or her. However, special care should be taken to ensure that the host is consumed by the communicant in the presence of the minister, so that no one goes away carrying the Eucharistic species in his hand. If there is a risk of profanation, then Holy Communion should not be given in the hand to the faithful.”

Receiving in the hand is outside of the norm within the Roman Rite, but is allowed in the United States. Furthermore, the Precious Blood should be received standing only. It is important to note the Host MUST be consumed in the presence of the Minister. The document also states that it is illicit for the faithful to take the Host for themselves from the hands or chalice of the Minister. It is also illicit for spouses to give Communion to each other. Communion should be received individually and not as a couple or group. The Priest and when necessity calls for it, the extraordinary ministers, are the only ones allowed to distribute Holy Communion. For those who wish to receive in the hand, it would be wise to keep the words of St. Cyril of Jerusalem in mind: “Make your left hand like a throne to support your right hand in order to receive the Celestial King. Treat the consecrated Host with great care, ensuring that pieces do not fall on the ground, just as we would not let pieces of gold fall to the ground.”

(Published in the Bulletin of May 17, 2015)

By Father Paul Wickens (Handbook for Parents by Neumann Press)

Yet, parents must do “everything” they can do to raise a child in the Faith and then trust that God will complete the work. I think there is a danger in thinking that a person is “done” at 18, that a child is “raised well” (or not) by then. After all, which of us is totally complete, finally the person God calls us to be even before we hit the second decade age mark? Moving towards God and towards Heaven takes an entire life’s work. In the early years, parents are critical in launching the child in this direction. Later on, the decision, responsibility, and privilege will be the child’s own. But it is a process, and we have to remember that. That being said, what should good parents know in order to raise their children well in the Faith? And what should parents do?

What Parents Should Know: Knowing several things will help Catholic parents navigate the exciting world of raising their children well. First, parents should know that the world, generally, will not support their efforts to raise their children in the Catholic faith. That’s not being negative. It’s stating a fact. Since the time Jesus walked the earth Christian beliefs and Christians themselves have been persecuted. We need to arm ourselves with a joyful demeanor and live the Christian live fully without expecting it to be easy or to be applauded. The world will frequently contradict our desires to be modest, chaste, kind, generous, patient, temperate, and holy. We must be all those things anyway. The world will tell us to pursue materialism, earthly goods, fame, power, and success. We must reject that and reach for higher goals—and teach our children to do the same. We have to expect to be revolutionaries, of sorts, radically living in peace, for Christ. And remember, revolutionaries don’t necessarily have support groups.

Yes, there may be pockets here and there of support, of like-minded people who are striving to raise their children the way that we are, and finding these folks will be blessed relief and consolation, like cold water is to a thirsty soul. Indeed, we should seek out like-minded parents to network and brainstorm with them, but we must not expect to rely on them in all cases, at all times. God alone will be our perfect strength as we seek to do His will in our families.

Second, parents should also know that children learn far more from example than from preaching or formal lessons. The best way we can raise good Catholic children is to be good Catholic people ourselves. Children learn temperance by seeing us model that. They learn kindness of speech by seeing that exemplified in us. They learn to love the Mass and Sacraments when we love the Mass and Sacraments and bring them with us to experience them. We don’t need to preach to children the importance of praying the Rosary, although sharing stories and the Church’s guidance in this regard is good. We need to give them little plastic rosaries when they are just toddlers and snuggle with them on our laps as we recite the mysteries and pray this prayer ourselves. Our Catholic faith must be totally and entirely integrated in our lives, both for our own good and so our children can absorb it.

Third, parents should know that perseverance is essential because suffering often comes with the territory of raising children. This can be difficult to understand when one is in the midst of it, especially at the beginning. We might initially address child-raising like we have other “projects”—by making a plan and giving it our best efforts. We expect immediate positive results because we have tried so hard and done our research. Yet, raising good Catholic children is not like any other “project”. It takes more time, more faith, more trust than anything else we have ever done. Sometimes situations arise in child-rearing that challenge us to the very core of ourselves and elicit suffering, sometimes great suffering. This is perfectly normal. You see, God molds us as we mold our children. These are “growing pains” of sorts. The growth toward holiness, in fact, should, be a family endeavor. If we stay close to Him, we have nothing to fear and are assured of “success” in His time and in His way.

One day when I was at Mass, I suddenly and surely felt that a distinct part of the vocation of mothers is to suffer for their children. I sincerely believe that when we unite our daily sufferings to those of Jesus on the cross, our suffering can be redemptive. Our children may be buoyed by our generosity and spirit of acceptance when they would otherwise be tempted to falter just by our offering our sufferings for them. The more children we have the more prayers we ought to be offering, and the more willing we ought to be to accept life’s little and big crosses for them. Our children’s eternal salvation may depend on it. I can’t help but think of good St. Monica who followed her selfish and sinful son to Rome, and then to Milan, literally hounding him with prayers. It is said that a bishop once said to a distraught Monica, “Surely a son of so many tears and prayers will not be lost.” And we all know the outcome of that story... St. Monica became a great saint, as did her son St. Augustine, who was also named a Doctor of the Church. We would all do well to emulate the example of St. Monica and be relentless prayer warriors for our children.

What Parents Should Do: There is no formula for raising good Catholic children into good Catholic adults, but we can utilize a strategy that has helped many parents and families. These 7 “R”s can help you in your parenting journey.

Receive the sacraments soon and frequently. This cannot be emphasized enough. Baptize babies immediately. It is most important that a child receives their baptism as soon as possible after birth. Make a family confession date every month. Some families like to go out for ice cream afterwards or another little treat. The sacrament of confession is critical for the spiritual growth of everyone. We wouldn’t dream of going months without showering, which cleanses our bodies, so why should we consider going more than a month without Confession, which cleanses our souls? Last, we should take our children to Mass every Sunday and Holy days of obligation. If your children are not in a Catholic school, enroll them in your parish’s Religious education program. Attend form kindergarten all the way through high school Confirmation. Don’t be Sacramental Catholics who come around only when it’s time to fulfill a Sacrament. As they grow older, puts sports and coaches second rather than first before the third commandment. If you don’t joyfully value and practice the Mass and sacraments, neither will your children who are watching you.

Read to your child.Start with simple toddler bible stories when they are small, then move on to other Catholic board books and short stories which teach the Faith in simple terms. Incorporate these into evening story time. As your child grows older, add the “real” bible, the catechism, enriching words from all sources. Take the time to teach your children simple apologetics. The complexity of the apologetics books chosen can grow with your child’s age and wisdom. Snuggling on the sofa with a good book and your child can be bonding like few things are, and will help your child grow in Faith if you choose the right reading.

Remember to pray - often - and together as a family. Teach them to talk to God regularly and teach them their prayers. Pray in the morning, the evening, at meals (even in public), when there’s trouble and when there is rejoicing. Teach them to talk to God often!

Remain steadfast. Endure and trust in Him.

Rely on God’s good graces. Trust Him.

Rejoice Be thankful. Enjoy each moment, each stage and yes, each challenge. As we strive to raise our children well we will see personal growth too. God is so good.

Relax Give yourself a break when you need one, and find ways to spiritually re-charge. Attend a bible study at your parish alone, take time for personal prayer, or meet a like-minded friend for lunch and exchange of ideas. Try hard but don’t expect perfection right off the bat. If you falter, forgive yourself and get up and try again. Remember a fool sits enjoying a mud puddle, but an equal fool may recognize his situation yet sits and laments his fate in the puddle without trying to get out. A wise person recognizes when she is deep “in the mud”, gets up, wipes herself off (Confession) and tries again, careful to avoid the puddle the next time. An eighth “R” might also be to recognize that “success” is not measured by external cues alone. God works in mysterious ways in the deep recesses of the human soul. He is working on our children as He is working on us. Trust Him.

A Ninth “R” – an addition by Rhonda Storey:

Review Be involved in their lives. Know where they are going, what they are watching and who their friends are. Stay involved in all aspects of their lives. Don’t let the TV, phones, iPads, lap tops etc. be their babysitters. As they become teens keep a close eye on their computer sites and phone apps. Talk with them about media topics and keep a constant open dialog with your kids. Talk about bullying and being a vigilant Christian. They will talk with you if you LISTEN. You are the first and most important teachers of YOUR children.

(Published in the Bulletins of May 24 and May 31, 2015)

By Ruben Beltran

“How Do We Know We Are Part of God's Family?” When we think about God we usually think of Him as Creator, Redeemer, or Sanctifier, but these words describe what God does in time and not who He is. Creation had a beginning, redemption was for creation, and God sanctifies that which He creates. Creation is not eternal but God is, so who is God from all eternity? St. Pope John Paul ll once said: “God in His deepest mystery is not a solitude, but a family, since He has in Himself Fatherhood, Sonship and the essence of the family, which is love.”

God is Father because He is eternally fathering the Son, and that interpersonal love between the Father and the Son is the Holy Spirit. Notice in the above quote that St. Pope John Paul ll did not say God is like a family but that He is a family. Every earthly family is an icon of the Most Holy Trinity. The Father gives His love to the Son, the Son receives that love, and then returns it to the Father, and that interpersonal love is the Holy Spirit. In the same way, the husband gives his love to his wife, the wife then receives that love, and then returns it to her husband, and that love between them creates a third person. The two become one and in so doing become three in one. But how do we know God is our Father and how do we know we are part of His family? Dr. Scott Hahn gives a great explanation:

“First, we live in His house. As members of the Catholic Church, we live in the house which Christ promised to build—as a wise man does—upon the rock (cf. Mt. 16:17–19; 7:24–27). ‘Christ was faithful over God’s house as a son. And we are His house if we hold fast our confidence and pride in hope’ (Heb. 3:6). So then you are no longer strangers and sojourners, but you are fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus Himself being the cornerstone (Eph. 2:19–20).

“Second, we are called by His name. In Baptism, we are marked for life in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit (Mt. 28:18–20). We ‘were sealed with the promised Holy Spirit, who is the guarantee of our inheritance until we acquire possession of it’ (Eph. 1:13–14). Our family unity is thus based upon the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace. There is one body and one Spirit, just as you were called to the one hope that belongs to your call, one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of us all (Eph. 4:3–6).

“Third, we sit at His table. We ‘partake of the table of the Lord’ (1 Cor. 10:21)—as God’s children—in the Eucharist, which Jesus instituted in the presence of His disciples ‘as they were at table eating’ (Mk. 14:18).