CATECHESIS Q & A: DEEPENING OUR KNOWLEDGE

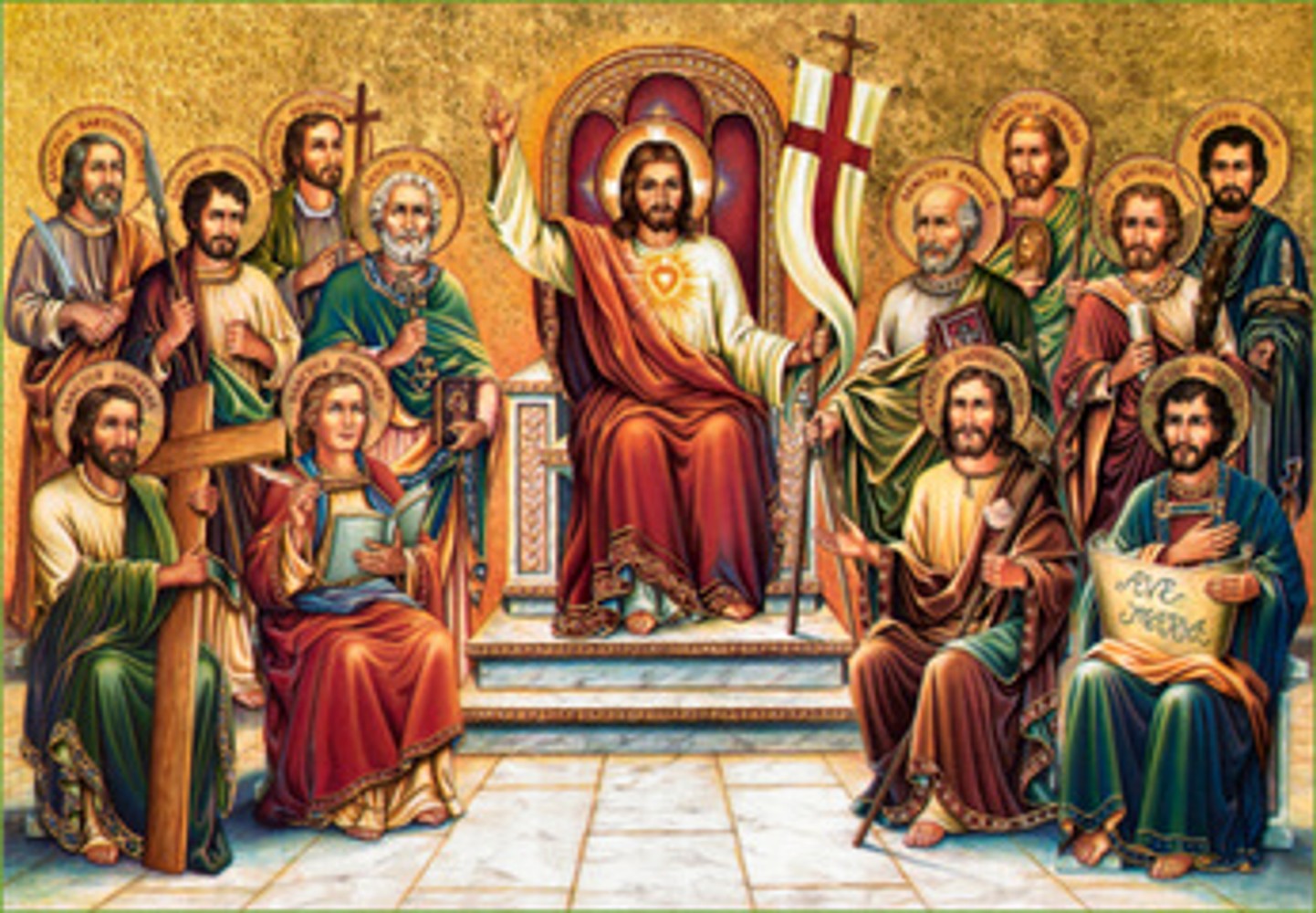

"What is Apostolic Succession?"

By Catholic Answers

What is Apostolic Succession? It is the line of bishops stretching back to the apostles; it’s the uninterrupted transmission of spiritual authority from the Apostles through successive popes and bishops. In order that the full and living Gospel might always be preserved in the Church, each of the twelve apostles left a bishop as his successor. Thus all priests, ordained by bishops in the apostolic succession, are also part of the succession. For biblical corroboration look at Acts 1:21-26, where the apostles acted swiftly to replace the Judas’ position. After choosing Matthias they laid hands on him to confer apostolic authority. Also in 1 Timothy 4:14, where Paul reminds Timothy that the office of bishop had been conferred on him through the laying on of hands.

The testimony of the early Church is deafening in its unanimous assertion of apostolic succession. Far from being discussed by only a few writers, the belief that the apostles handed on their authority to others was one of the most frequently and vociferously defended doctrines in the first centuries of Christianity.

Article No. 54 (Published in the Bulletin of June 19, 2016)

If you would like to read a more comprehensive explanation, here is the published study of the International Theological Commission, made in 1973:

This study sets out to throw light on the concept of apostolic succession, on the one hand, because a clear presentation of the Catholic doctrine would seem to be useful to the Catholic Church as a whole, and, on the other hand, because it is demanded by ecumenical dialogue. For some time now ecumenical dialogue has been going on in various parts of the world, and it has a promising future provided the Catholics taking part in it remain faithful to their Catholic identity. So we propose to present the Catholic teaching on apostolic succession in order to strengthen our brothers in the Faith and to contribute to the mature development of ecumenical dialogue.

We begin by listing some of the difficulties that are frequently encountered:

1. What can be deduced, scientifically, from the witness of the New Testament? How can one show the continuity between the New Testament and the Church’s Tradition?

2. What is the place of the imposition of hands in apostolic succession?

3. Is there not a tendency in some quarters to reduce apostolic succession to the apostolicity that is common to the whole Church, or, conversely, to reduce the apostolicity of the Church to apostolic succession?

4. How can one evaluate the ministry of other churches and Christian communities in relation to apostolic succession?

Behind all these questions lies the problem of the relationship between Scripture, Tradition, and the dogmatic pronouncements of the Church. The dominant note in our thinking is provided by the vision of the Church as willed by the Father, emerging from Christ’s Paschal mystery, animated by the Holy Spirit, and organically structured. We hope to set the specific and essential function of apostolic succession in the context of the whole Church, which confesses its apostolic Faith and bears witness to its Lord.

We rely upon Scripture, which has for us a twofold value as a historical record and an inspired document. Insofar as it is a historical record, Scripture recounts the most important events in the mission of Jesus and the life of the Church of the first century; insofar as it is an inspired document, it bears witness to certain facts and at the same time interprets them and reveals their inner significance and dynamic coherence. As an expression of the thought of God in the words of men, Scripture has a normative value for the thinking of Christ’s Church in every age.

But any interpretation of Scripture that regards it as inspired and therefore normative for all ages is necessarily an interpretation that takes place within the Church’s Tradition, which recognizes Scripture as inspired and normative. The recognition of the normative character of Scripture fundamentally implies a recognition of that Tradition within which Scripture itself was formed and came to be considered and accepted as inspired. The normative status of Scripture and its relationship to Tradition go hand in hand. The result is that any theological considerations about Scripture are at the same time ecclesial considerations.

This, then, is the methodological starting point of the document: any attempt to reconstitute the past by selecting isolated phrases from the New Testament Tradition and separating them from the way they were received in the living Tradition of the Church is contradictory. The theological approach that sees Scripture as an indivisible whole and that links it with the life and thought of the early community that acknowledges and "recognizes" it as Scripture certainly does not mean that properly historical judgments are eliminated in advance by an ecclesiological a priori, which would make impossible an interpretation in conformity with the demands of historical method.

The method adopted here enables one to grasp the limitations of pure historicism: it admits that the purely historical analysis of a book in isolation from its effects and influence cannot show with certainty that the way Faith actually developed in history was the only possible way But these limits to historical proof, which one cannot doubt, do not destroy the value and weight of historical knowledge. On the contrary, the fact that the early Church accepted Scripture as constitutive is something to be constantly meditated upon: that is, we have to think out again and again the relationship, the differences, and the unity between the different elements.

That also means that one cannot dissolve Scripture into a series of unrelated sketches, each one of which would be an attempt to express a lifestyle founded on Jesus of Nazareth, but rather that one must understand it as the expression of a historical unfolding path that reveals the unity and the catholicity of the Church. There are three broad stages along this path: the time before Easter, the apostolic period, and the subapostolic period, and each period has its own specific value; it is significant that what the dogmatic constitution "On Divine Revelation", Dei Verbum (18), calls "viri apostolici" should be responsible for some of the New Testament writings.

This helps one to see clearly how the community of Jesus Christ solved the problem of remaining apostolic even though it had become subapostolic. This explains why the subapostolic part of the New Testament has a normative character for the Church at a later period, for it must build on the apostles, who themselves have Christ as their foundation. In the subapostolic writings, Scripture itself bears witness to Tradition and gives evidence of the Magisterium in that it recalls the teaching of the apostles (see Acts 2:42; 2 Pet 1:20). This Magisterium really begins to develop in the second century, at the time when the idea of apostolic succession is made fully explicit.

Scripture and Tradition taken together, pondered upon and authentically interpreted by the Magisterium, faithfully transmit to us the teaching of Christ our Lord and Savior and determine the doctrine that it is the Church’s mission to proclaim to all peoples and to apply to each generation until the end of the world. It is in this theological perspective — fully in accord with the doctrine of Vatican II — that we have written this document on apostolic succession and evaluated the ministries that exist in churches and communities not yet in full communion with the Catholic Church.

I. THE APOSTOLICITY OF THE CHURCH AND THE COMMON PRIESTHOOD

1. The creeds confess their Faith in the apostolicity of the Church. That means not simply that the Church continues to hold the apostolic Faith but that it is determined to live according to the norm of the primitive Church, which derived from the first witnesses of Christ and was guided by the Holy Spirit, who was given to the Church by Christ after his Resurrection. The Epistles and the Acts of the Apostles show how effective was this presence of the Spirit in the whole Church, and that he ensured not only its diffusion but also and more importantly the transformation of hearts: the Spirit assimilates them to Christ and his feelings. Stephen, the first martyr, repeats the words of forgiveness of his dying Lord; Peter and John are beaten and rejoice that they should be found worthy to suffer with him; Paul bears in his body the marks of Christ (Gal 6:17), wants to be conformed to the death of Christ (Phil 3:10), to know nothing save the crucified One (1 Cor 1:23; 2:2), and he considers his whole life as an assimilation to the expiating sacrifice of the Cross (Phil 2:17; Col 1:24).

2. This assimilation to the "thoughts" of Christ and above all to his sacrificial death for the world gives ultimate meaning to the lives of those who want to lead a Christian, spiritual, and apostolic life. That is why the early Church adapted the priestly vocabulary of the Old Testament to Christ, the Paschal Lamb of the New Covenant (1 Cor 5:7), and then to Christians whose lives are defined in relation to the Paschal mystery of Christ. Converted by the preaching of the Gospel, they are convinced that they are living out a holy and royal priesthood that is a spiritual transposition of the priesthood of the Old Testament (1 Pet 2:5-9; see Ex 19:6; Is 61:6) and that was made possible by the sacrificial offering of him who recapitulates in himself all the sacrifices of the Old Law and opens the way for the complete and eschatological sacrifice of the Church (see St. Augustine, De civitate Dei 10, 6).

Christians as living stones in the new building that is the Church founded on Christ offer to God worship in the Spirit who has made them new; their cult is both personal, since they have to "present their bodies as a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to God" (Rom 12:1; see 1 Pet 2:5), and communal, since together they make up the "spiritual house", the "royal priesthood" and "holy nation" (1 Pet 2:9), whose purpose is to offer "spiritual sacrifices that Jesus Christ has made acceptable to God", (1 Pet 2:8).

This priesthood has a moral dimension—since it must be exercised every day and in ordinary situations—and an eschatological dimension, since it is, in eternity to come that Christ has promised to make of us "a line of kings, priests to serve his God and Father" (Rev 1:6; see 5:10; 20:6); but it has also a cultural dimension, since the Eucharist by which they live is compared by Saint Paul to the sacrifices of the Old Law and even - though only to make a sharp contrast - to pagan sacrifices (1 Cor 10:16-21).

3. Now Christ instituted a ministry for the establishment, animation, and maintenance of this priesthood of Christians. This ministry was to be the sign and the instrument by which he would communicate to his people in the course of history the fruits of his life, death, and Resurrection. The first foundations of this ministry were laid when he called the Twelve, who at the same time represent the new Israel as a whole and, after Easter, will be the privileged eyewitnesses sent out to proclaim the Gospel of salvation and the leaders of the new people, "fellow workers with God for the building of his temple" (see 1 Cor 3:9). This ministry has an essential function to fulfill toward each generation of Christians. It must therefore be transmitted from the apostles by an unbroken line of succession. If one can say that the Church as a whole is established upon the foundation of the apostles (Eph 2:20; Rev 21:14), one has to add that this apostolicity, which is common to the whole Church, is linked with the ministerial apostolic succession, and that this is an inalienable ecclesial structure at the service of all Christians.

II. THE ORIGINALITY OF THE APOSTOLIC FOUNDATION OF THE CHURCH

The apostolic foundation has this special characteristic: it is both historical and spiritual.

It is historical in the sense that it comes into being through an act of Christ during his earthly existence: the call of the Twelve at the start of his public ministry, their commission to represent the new Israel and to be involved ever more closely with his Paschal journey, which is consummated in the Cross and Resurrection (Mk 1:17; 3:14; Lk 22:28; Jn 15:16). Far from destroying the pre-Easter structure, the Resurrection confirms it. In a special manner Christ makes the Twelve the witnesses of his Resurrection, and they head the list that he had ordered before his death: the earliest confession of Faith in the Risen One includes Peter and the Twelve as the privileged witnesses of his Resurrection (1 Cor).

Those who had been associated with Jesus from the beginning of his ministry to the eve of his Paschal death are able to bear public witness to the fact that it is the same Jesus who is risen (Jn 15:27). After Judas’ defection and even before Pentecost, the first concern of the Eleven is to replace him in their apostolic ministry with one of the disciples who had been with Jesus since his baptism, so that with them he could be a witness of his Resurrection (Acts 1:17-22). Moreover Paul, who was called to the apostolate by the risen Lord himself and thus became part of the Church’s foundation, is aware of the need to be in communion with the Twelve.

This foundation is not only historical; it is also spiritual. Christ’s pass-over, anticipated at the Last Supper, establishes the New Covenant and thus embraces the whole of human history. The mission and task of preaching the Gospel, governing, reconciling, and sanctifying that are entrusted to the first witnesses cannot be restricted to their lifetime. As far as the Eucharist is concerned, Tradition—whose broad lines are already laid down from the first century (see Lk and Jn)—declares that the apostles’ participation in the Last Supper conferred on them the power to preside at the eucharistic celebration.

Thus the apostolic ministry is an eschatological institution. Its spiritual origins appear in Christ’s prayer, inspired by the Holy Spirit, in which he discerns, as in all the great moments of his life, the will of the Father (Lk 6:12). The spiritual participation of the apostles in the mystery of Christ is completed fully by the gift of the Holy Spirit after Easter (Jn 20:22; Lk 24:44-49). The Spirit brings to their minds all that Jesus had said (Jn 14:26) and leads them to a fuller understanding of his mystery (Jn 16:13-15).

The kerygma, if it is to be properly understood, must not be separated or treated in abstraction from the Faith to which the Twelve and Paul came by their conversion to the Lord Jesus or from the witness to him manifested in their lives.

III. THE APOSTLES AND APOSTOLIC SUCCESSION IN HISTORY

The documents of the New Testament show that in the early days of the Church and in the lifetime of the apostles there was diversity in the way communities were organized, but also that there was, in the period immediately following, a tendency to assert and strengthen the ministry of teaching and leadership. Those who directed communities in the lifetime of the apostles or after their death have different names in the New Testmanet. In comparison with the rest of the Church, the feature of the presbyteroi-episkopoi is their apostolic ministry of teaching and governing. Whatever the method by which they are chosen, whether through the authority of the Twelve or Paul or some link with them, they share in the authority of the apostles who were instituted by Christ and who maintain for all time their unique character.

In the course of time this ministry underwent a development. This development happened by internal necessity. It was encouraged by external factors, and above all by the need to maintain unity in communities and to defend them against errors. When communities were deprived of the actual presence of apostles and yet still wanted to refer to the authority, there had to be some way of continuing to exercise adequately the functions that the apostles had exercised in and in relation to them.

Already in the New Testament texts there are echoes of the transition from the apostolic period to the subapostolic age, and one begins to see signs of the development that in the second century led to the stabilization and general recognition of the episcopal ministry. The stages of this development can be glimpsed in the last writings of the Pauline Tradition and in other texts linked with the authority of the apostles.

The significance of the apostles at the time of the foundation of the earliest Christian communities was held to be essential for the structure of the Church and local communities in the thinking of the subapostolic period. The principle of the apostolicity of the Church elaborated in this reflection led to the recognition of the ministry of teaching and governing as an institution derived from Christ by and through the mediation of the apostles. The Church lived in the certain conviction that Jesus, before he left this world, sent the Twelve on a universal mission and promised that he would be with them at all times until the end of the world (Mt 28:18-20). The time of the Church, which is the time of this universal mission, is therefore contained within the presence of Christ, which is the same in the apostolic period and later and which takes the form of a single apostolic ministry.

As one can see from the New Testament writings, conflicts could not always be avoided between individuals and communities and the authority of the ministry. Paul, on the one hand, strove to understand the Gospel with and in the community and so to work out with them norms for Christian life, but, on the other hand, he appealed to his apostolic authority whenever it was a matter of the truth of the Gospel (see Gal) or unyielding principles of Christian life (see 1 Cor 7 and so on).

Likewise, the ministry of governing should never be separated from the community in such a way as to place itself above it: its role is one of service in and for the community. But when the New Testament communities accept apostolic government, whether from the apostles themselves or their successors, then they obey and relate the authority of the ministry to that of Christ himself.

The absence of documents makes it difficult to say precisely how these transitions came about. By the end of the first century the situation was that the apostles or their closest helpers or eventually their successors directed the local colleges of episkopoi andpresbyteroi. By the beginning of the second century the figure of a single bishop who is the head of the communities appears very clearly in the letters of Saint Ignatius of Antioch, who further claims that this institution is established "unto the ends of the earth" (Ad Epk. 3, 2).

During the second century and after the Letter of Clement this institution is explicitly acknowledged to carry with it the apostolic succession. Ordination with imposition of hands, already witnessed to in the pastoral Epistles, appears in the process of clarification to be an important step in preserving the apostolic Tradition and guaranteeing succession in the ministry. The documents of the third century (Tradition of Hippolytus) show that this conviction was arrived at peacefully and was considered to be a necessary institution.

Clement and Irenaeus develop a doctrine on pastoral government and on the word in which they derive the idea of apostolic succession from the unity of the word, the unity of the mission, and the unity of the ministry of the Church; thus apostolic succession became the permanent ground from which the Catholic Church understood its own nature.

IV. THE SPIRITUAL ASPECT OF APOSTOLIC SUCCESSION

If after this historic survey we try to understand the spiritual dimensions of apostolic succession, we will have to stress first of all that the ordained ministry, although it represents the Gospel with authority and is essentially a service toward the whole Church, nevertheless demands that the minister should make Christ present in his humility (2 Cor 4:5) and make present Christ crucified (see Gal 2:19ff.; 16:14; 1 Cor 4:9ff.).

The Church that it serves is informed and moved by the Spirit, and "Church" here means the Church as a whole and in its members, for everyone who is baptized is "taught by the Spirit" (1 Thess 4:9; see Heb 8:11; Jer 31:33ff.; 1 Jn 2:20; Jn 6:45). The role of the priestly ministry is therefore to bring to mind authoritatively what is already embryonically included in baptismal Faith but can never be fully realized here below. Likewise the believer should nourish his Faith and his Christian life through the sacramental mediation of the divine life. The norm of Faith - which is formally known as the regula fidei - becomes immanent in Christian life thanks to the Spirit while it remains transcendent in relation to men, since it can never be purely an individual matter but is rather by its very nature ecclesial and catholic.

Thus in the rule of Faith the immediacy of the divine Spirit in each individual is necessarily linked to the communitarian form of this Faith. Paul’s statement is still valid: "No one can say ‘Jesus is the Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit" (1 Cor 2:3)—without the conversion that the Spirit is always ready to grant to human hearts, no one can recognize Jesus as the Son of God, and only those who know him as the Son will know the one whom Jesus calls "Father" (see Jn 14:7; 8:19; and so on). Since, therefore, it is the Spirit who brings us knowledge of the Father through Jesus, Christian Faith is trinitarian: its pneumatic or spiritual formnecessarily implies the content that is realized sacramentally in baptism in the name of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

The regula fidei, that is, the sort of baptismal catechesis in which the trinitarian content of Faith is developed, constitutes in its form and content the permanent basis for the apostolicity and catholicity of the Church. It realizes apostolicity because it binds those who preach the Faith to the christopneumatological norm: they do not speak in their own name but bear witness to what they have heard (see Jn 7:18; 16:13ff.).

Jesus Christ shows that he is the Son in that he proclaims that he comes from the Father. The Spirit shows that he is the Spirit of the Father and the Son, because he does not devise something of his own but reveals and recalls what comes from the Son (Jn 16:13). This prolongation of the work of Christ and of his Spirit gives apostolic succession its distinctive character and makes the Church’s Magisterium distinct from both the teaching authority of scholars and the rule of authoritarian power.

If the teaching authority were to fall into the hands of professors, Faith would depend upon the lights of individuals and would be thereby exposed to influence from the Zeitgeist, the spirit of the age. And where Faith depends upon the despotic power of certain individuals or groups, who themselves would decide what the norm was, then truth is replaced by arbitrary power. The true Magisterium, on the contrary, is bound by the word of the Lord and thus ushers those who listen to it into the realm of liberty.

Nothing in the Church can forego this need to refer to the apostles. Pastors and their flocks cannot avoid it; statements of Faith and moral precepts must be measured by it. The ordained ministry is bound to this apostolic mediation in a double way, since on the one hand it must submit to the norm of Christian origins and on the other hand it has the duty of learning from the community of believers, who themselves have the duty to instruct it.

We draw two conclusions from what has just been said:

1. No preacher of the Gospel has the right to proclaim the Gospel according to personal theories he may happen to have. He proclaims the Faith of the apostolic Church and not his own personality or his own religious experience.

This implies that we must add a third element to those we have already mentioned as belonging to the rule of Faith - form and content: the rule of Faith presupposes a witness who has been entrusted with a mission, who does not authorize him to speak, and that no individual community can authorize him to speak; and this comes about in virtue of the transcendence of the word. Authorization can only be given sacramentally through those who have already received the mission. It is true that the Spirit can freely arouse in the Church various charisms of evangelization and service and inspire all Christians to bear witness to their Faith, but these activities should be exercised with reference to the three elements mentioned in the regula fidei (see LG 12).

2. This mission (trinitarian in its basis) enters into the rule of Faith and implies a reference to the catholicity of Faith, which is at once a consequence of apostolicity and a condition of its permanence. For no individual and no community by itself has this power to send on a mission. It is only in relation with the whole - kath’holon, catholicity in time and in space - that permanence in mission can be guaranteed. In this way catholicity explains why the believer, as a member of the Church, is introduced into an immediate participation in the trinitarian life through the mediation not only of the God-Man but of the Church who is intimately associated with him.

Because of the catholic dimension of its truth and its life, the mediation of the Church has to be achieved in an ordered way, through a ministry that is given to the Church as one of its constitutive elements. This ministry does not have as its only point of reference a historical period that is now no more (and that is represented by a series of documents); given this reference back, it must be endowed with the power of representing in itself its Source, the living Christ, through an officially authorized proclamation of the Gospel and by authoritative celebration of sacramental acts, above all the Eucharist.

V. APOSTOLIC SUCCESSION AND ITS TRANSMISSION

Just as the divine Word made Flesh is itself both proclamation and the communicating principle of the divine life into which it brings us, so the ministry of the word in its fullness and the sacraments of Faith, especially the Eucharist, are the means by which Christ continues to be for mankind the ever-present event of salvation. Pastoral authority is simply the responsibility that the apostolic ministry has for the unity of the Church and its development, while the word is the source of salvation and the sacraments are both the manifestation and the locus of its realization.

Thus apostolic succession is that aspect of the nature and life of the Church that shows the dependence of our present-day community on Christ through those whom he has sent. The apostolic ministry is, therefore, the sacrament of the effective presence of Christ and of his Spirit in the midst of the people of God, and this view in no way underestimates the immediate influence of Christ and his Spirit on each believer.

The charism of apostolic succession is received in the visible community of the Church. It presupposes that someone who is to enter the ministry has the Faith of the Church. The gift of ministry is granted in an act that is the visible and efficacious symbol of the gift of the Spirit, and this act has as its instrument one or several of those ministers who have themselves entered the apostolic succession.

Thus the transmission of the apostolic ministry is achieved through ordination, including a rite with a visible sign and the invocation of God (epiklesis) to grant to the ordinand the gift of his Holy Spirit and the powers that are needed for the accomplishment of his task. This visible sign, from the New Testament onward, is the imposition of hands (see LG 21). The rite of ordination expresses the truth that what happens to the ordinand does not come from human origin and that the Church cannot do what it likes with the gift of the Spirit.

The Church is fully aware that its nature is bound up with apostolicity and that the ministry handed on by ordination establishes the one who has been ordained in the apostolic confession of the truth of the Father. The Church, therefore, has judged that ordination, given and received in the understanding she herself has of it, is necessary to apostolic succession in the strict sense of the word.

The apostolic succession of the ministry concerns the whole Church, but it is not something that derives from the Church taken as a whole but rather from Christ to the apostles and from the apostles to all bishops to the end of time.

VI. TOWARD AN EVALUATION OF NON-CATHOLIC MINISTRIES

The preceding sketch of the Catholic understanding of apostolic succession now enables us to give in broad outline an evaluation of non-Catholic ministries. In this context it is indispensable to keep firmly in mind the differences that have existed in the origins and in the subsequent development of these churches and communities, as also their own self-understanding.

1. In spite of a difference in their appreciation of the office of Peter, the Catholic Church, the Orthodox church, and the other churches that have retained the reality of apostolic succession are at one in sharing a basic understanding of the sacramentality of the Church, which developed from the New Testament and through the Fathers, notably through Irenaeus. These churches hold that the sacramental entry into the ministry comes about through the imposition of hands with the invocation of the Holy Spirit, and that this is the indispensable form for the transmission of the apostolic succession, which alone enables the Church to remain constant in its doctrine and communion. It is this unanimity concerning the unbroken coherence of Scripture, Tradition, and sacrament that explains why communion between these churches and the Catholic Church has never completely ceased and could today be revived.

2. Fruitful dialogues have taken place with Anglican communions, which have retained the imposition of hands, the interpretation of which has varied. We cannot here anticipate the eventual results of this dialogue, which has as its object to inquire how far factors constitutive of unity are included in the maintenance of the imposition of hands and accompanying prayers.

3. The communities that emerged from the sixteenth-century Reformation differ among themselves to such an extent that a description of their relationship to the Catholic Church has to take account of the many individual cases. However, some general lines are beginning to emerge. In general it was a feature of the Reformation to deny the link between Scripture and Tradition and to advocate the view that Scripture alone was normative. Even if later on some sort of place for Tradition is recognized, it is never given the same position and dignity as in the ancient Church. But since the sacrament of orders is the indispensable sacramental expression of communion in the Tradition, the proclamation of sola scriptura led inevitably to an obscuring of the older idea of the Church and its priesthood.

Thus through the centuries, the imposition of hands either by men already ordained or by others was often in practice abandoned. Where it did take place, it did not have the same meaning as in the Church of Tradition. This divergence in the mode of entry into the ministry and its interpretation is only the most noteworthy symptom of the different understandings of Church and Tradition. There have already been a number of promising contacts that have sought to reestablish links with the Tradition, although the break has so far not been successfully overcome.

In such circumstances, intercommunion remains impossible for the time being, because sacramental continuity in apostolic succession from the beginning is an indispensable element of ecclesial communion for both the Catholic Church and the Orthodox churches.

To say this is not to say that the ecclesial and spiritual qualities of the Protestant ministers and communities are thereby negligible. Their ministers have edified and nourished their communities. By baptism, by the study and the preaching of the word, by their prayer together and celebration of the Last Supper, and by their zeal they have guided men toward faith in the Lord and thus helped them to find the way of salvation. There are thus in such communities elements that certainly belong to the apostolicity of the unique Church of Christ.