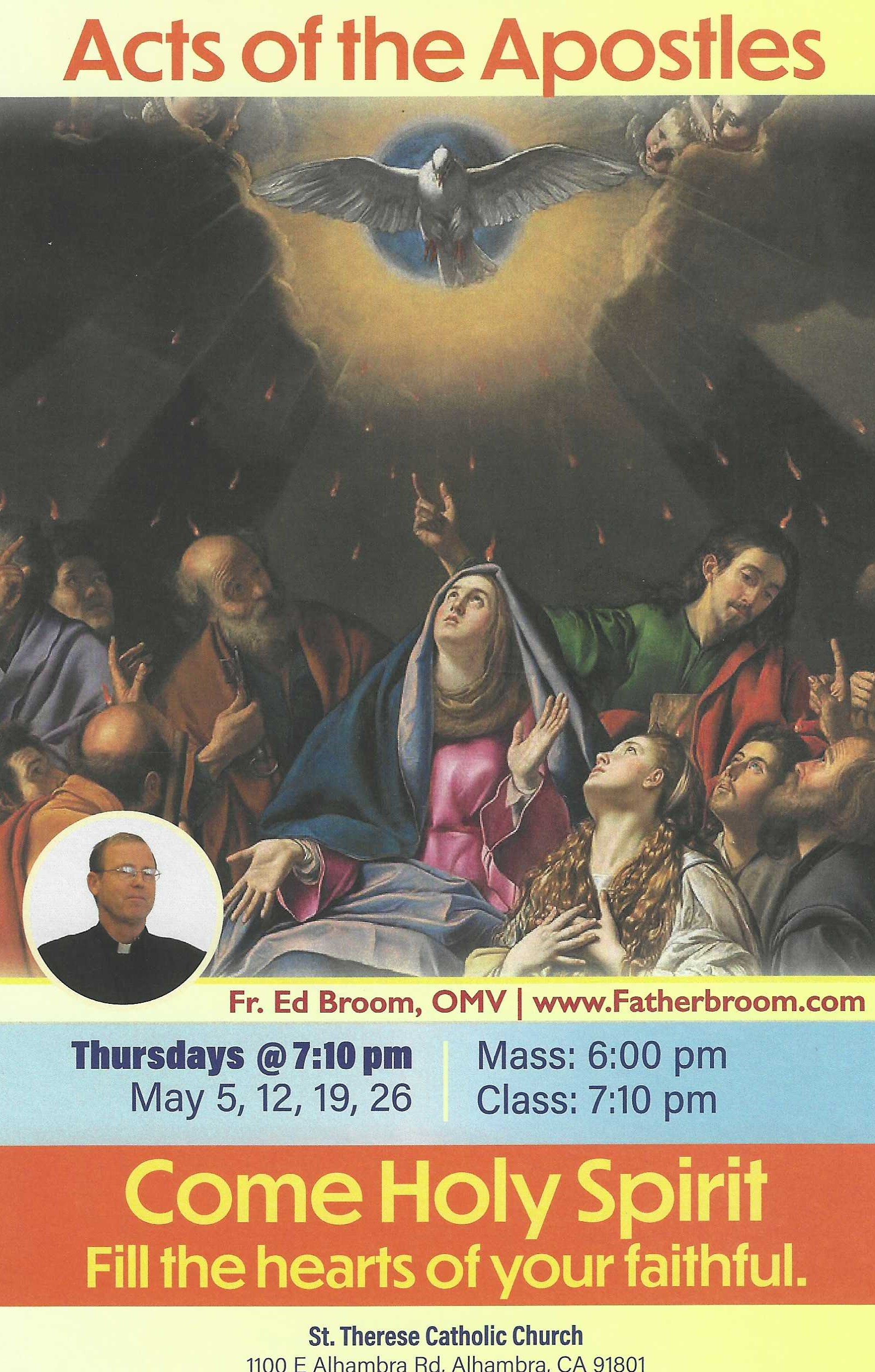

F E A T U R E D E V E N T

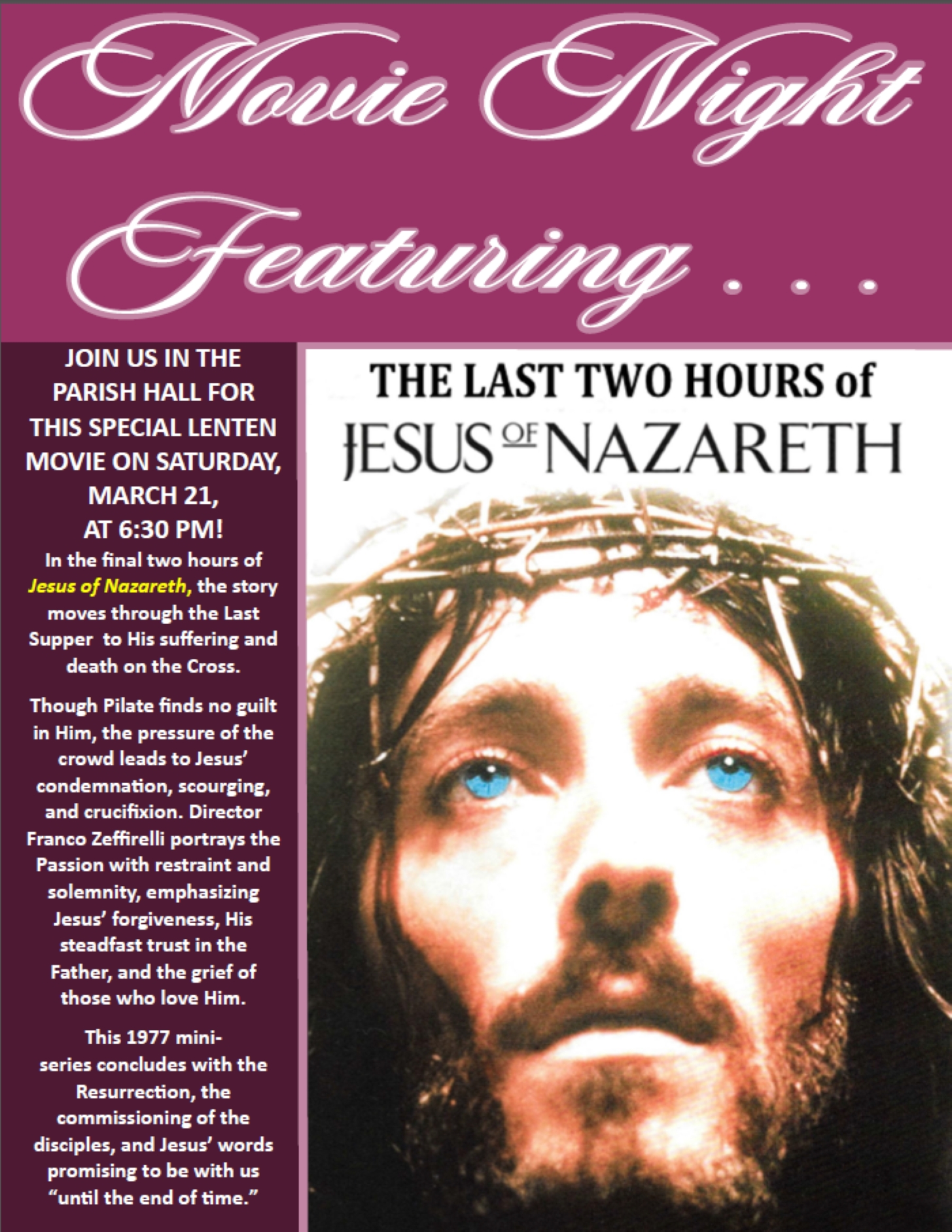

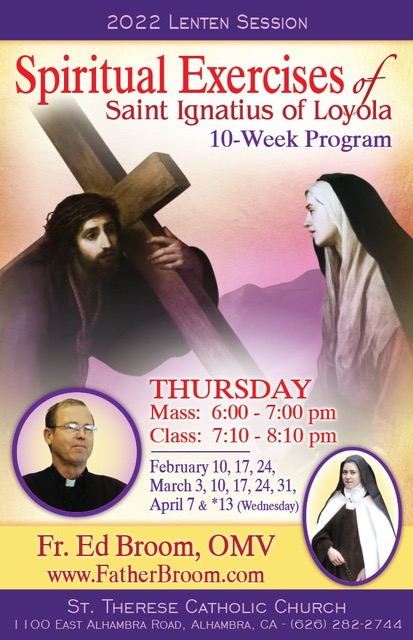

W H A T ' S H A P P E N I N G FOR L E N T ?

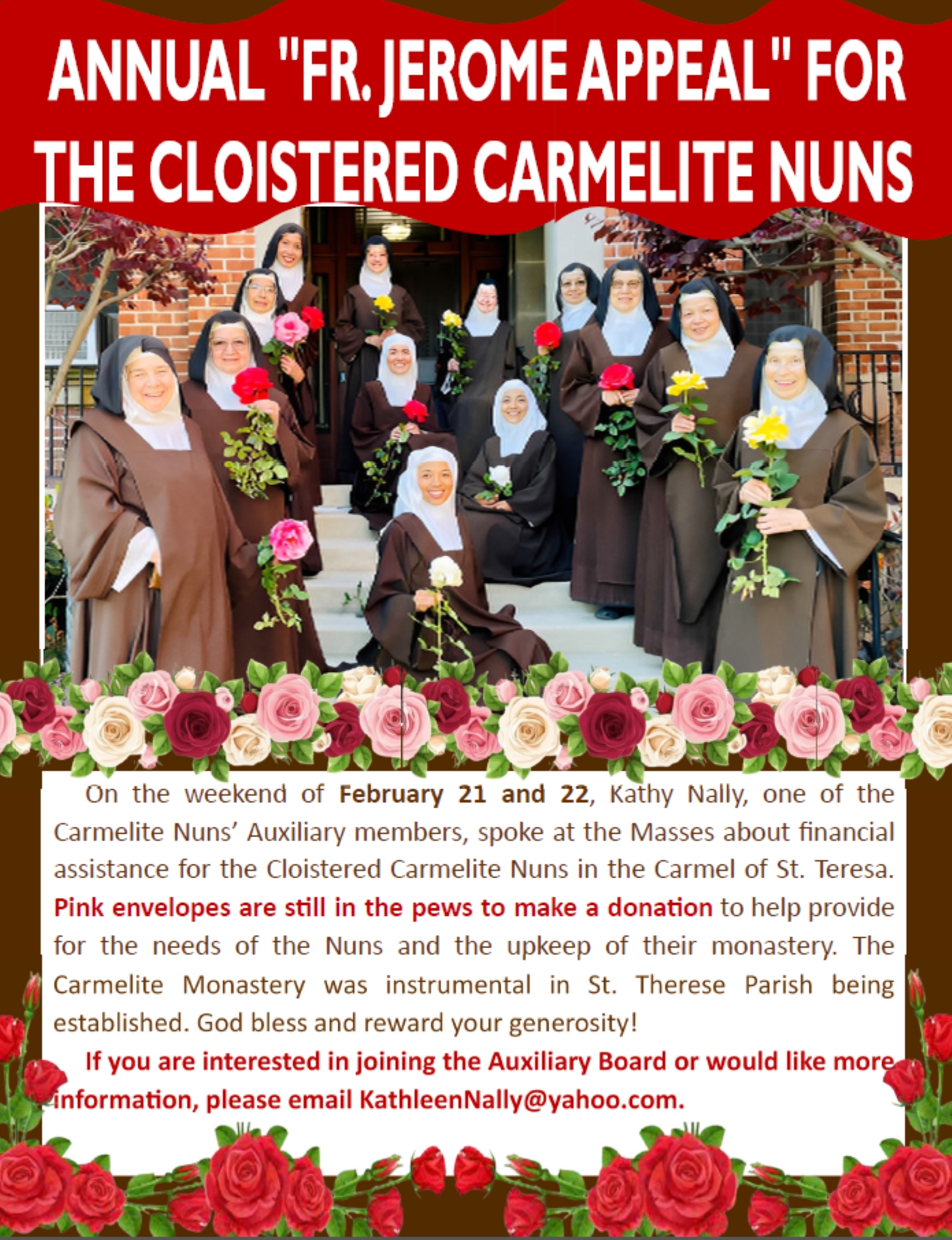

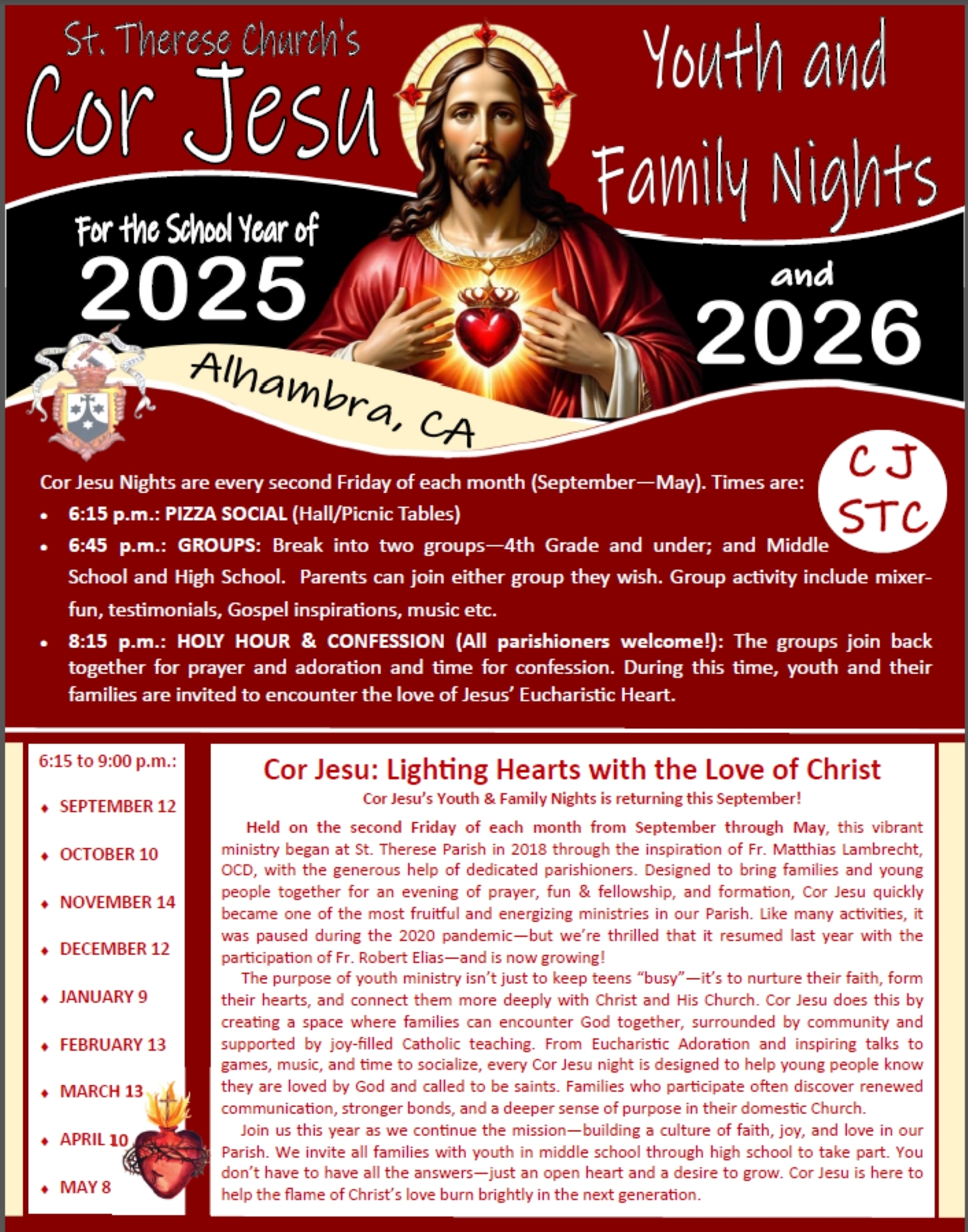

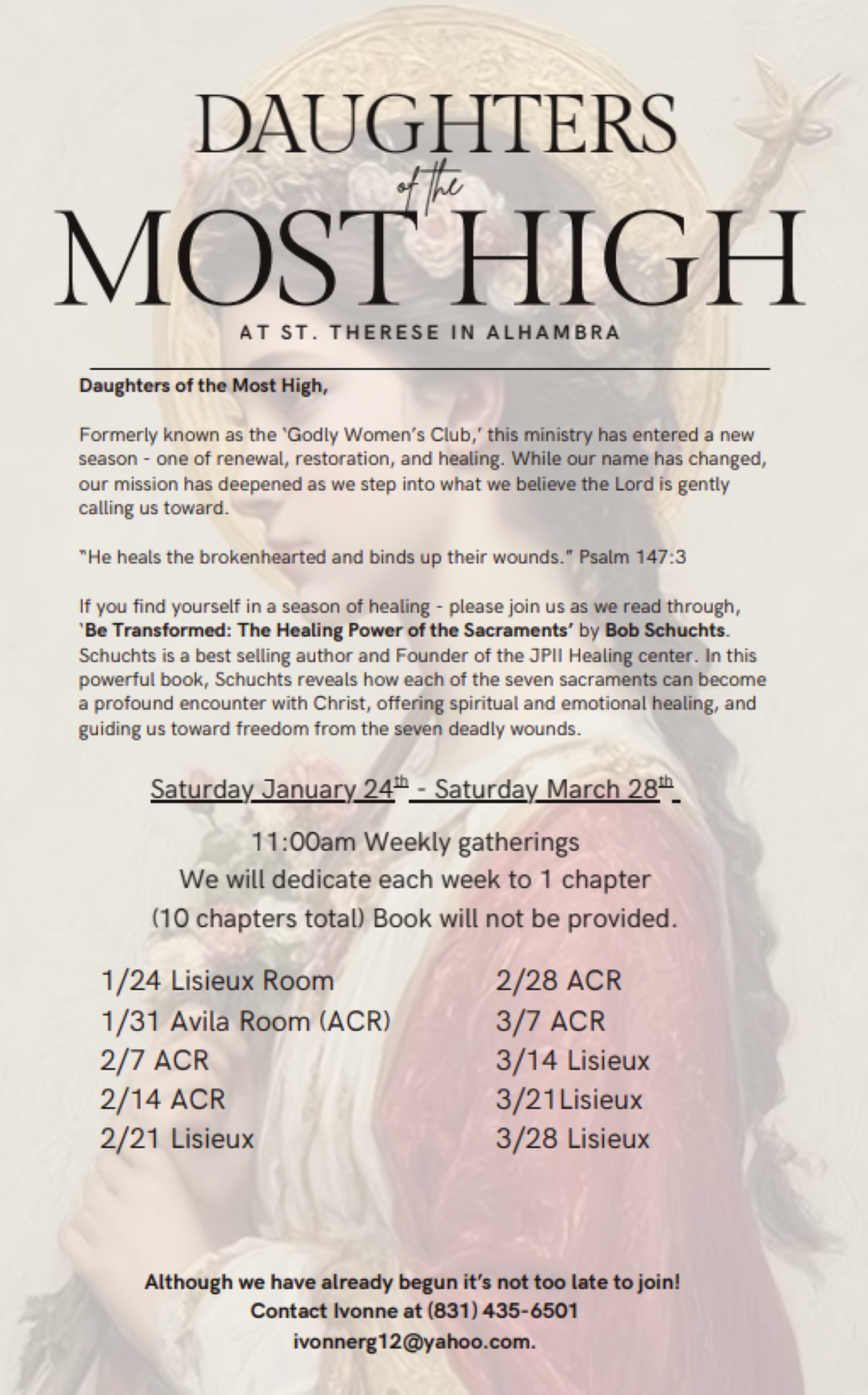

O T H E R P A R I S H E V E N T S

BE SURE TO ALSO CHECK OUT THE "OUTSIDE THE PARISH" SECTION (IMMEDIATELY BELOW THIS SECTION)

Clicking any of the "flyers" will either enlarge them for easy reading or take you to a related website for more info.

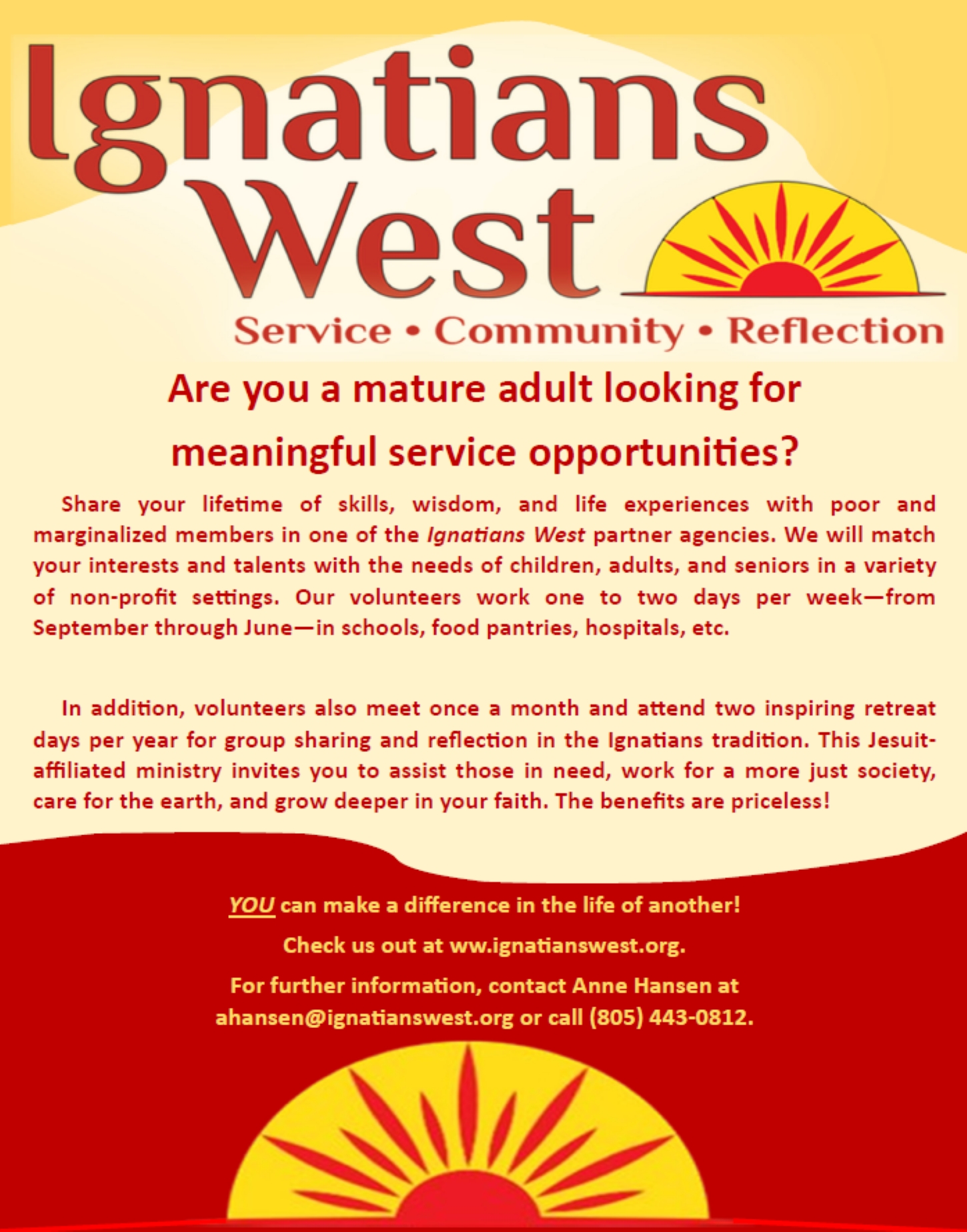

O U T S I D E T H E P A R I S H

Click on the two pilgrimage flyers below for the complete itineraries and an application. Once opened, scroll down.

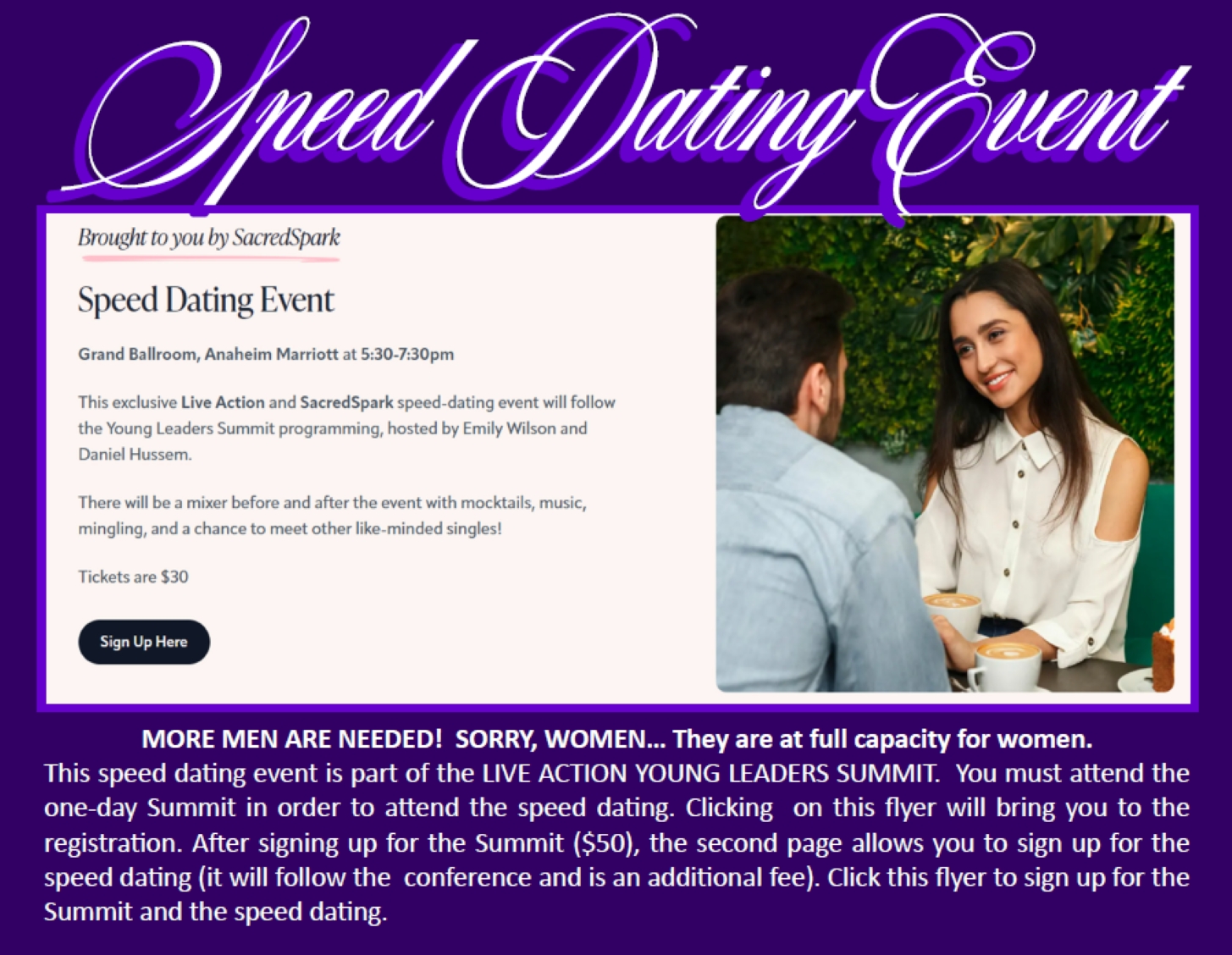

YOUNG ADULTS - CLICK THE FLYER BELOW TO ATTEND A ONE-DAY CONFERENCE... THEN, IF INTERESTED IN ATTENDING A SPEED DATING EVENT AT THE END OF THE CONFERENCE, ADD THAT TO YOUR TICKET FOR AN ADDITIONAL $30... SPEED DATING IS FILLED FOR WOMEN.. MEN ARE STILL NEEDED.... (MORE INFO ABOUT THE SPEED DATING ON THE SECOND FLYER BELOW).

THE CONFRATERNITY OF THE BROWN SCAPULAR OF THE CARMELITE ORDER

Click on the picture below to go to the Confraternity website (set up by the Discalced Carmelite Friars)

You will find information for both those who are not enrolled and also for those who already are.

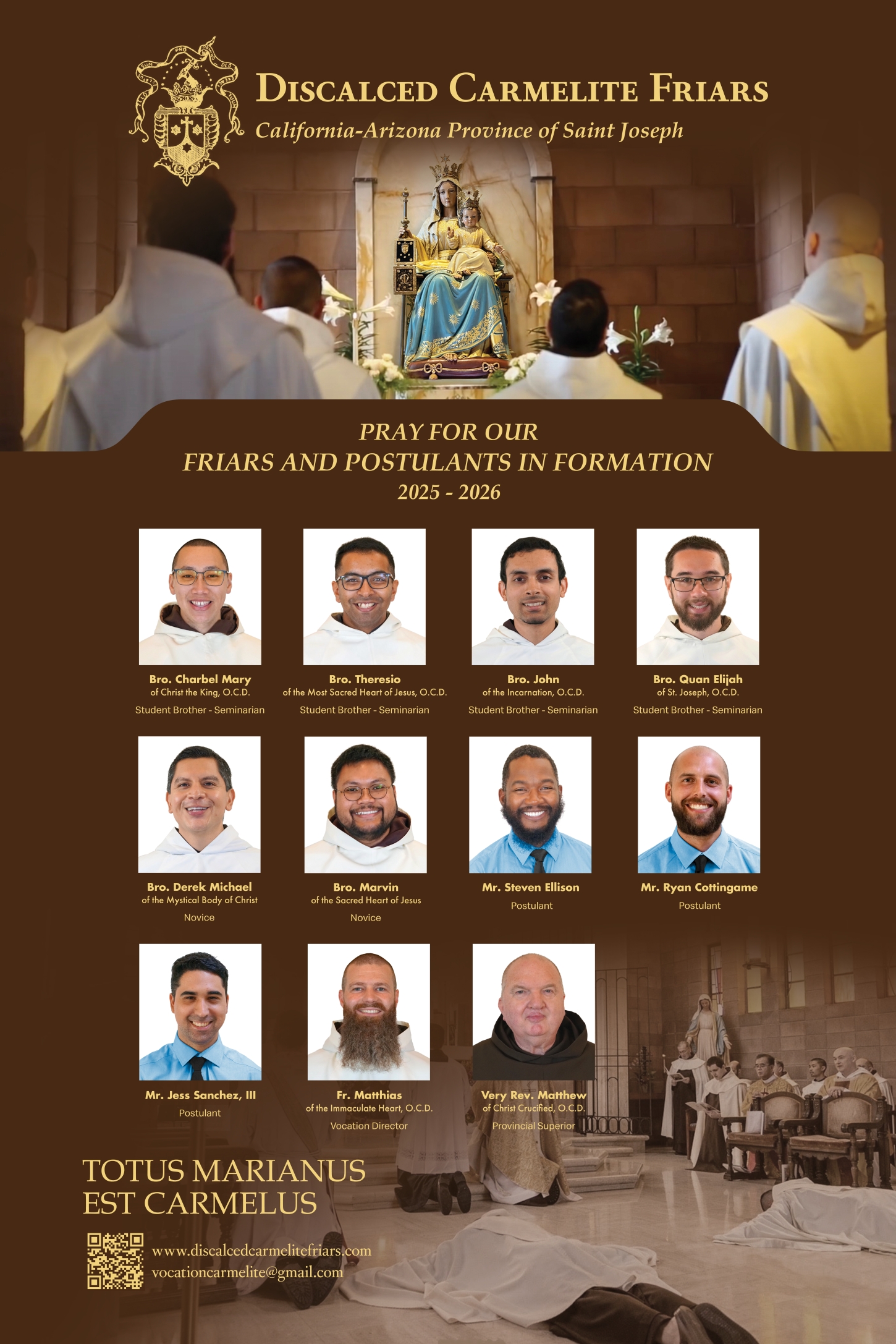

CARMELITE NEWS AND INFORMATION

CARMELITE VOCATION NEWSLETTER

Fr. Matthias Lambrecht, Vocation Director for the Discalced Carmelite Friars' Western Province, has shared with us the latest Carmelite Vocation Newsletter (Summer 2025). Click the image below to meet our current Carmelite postulants, novices, and seminarians--as well as all those who are discerning religious life with the Carmelite Friars.

Please keep them all in your prayers!

GFGGGFGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG

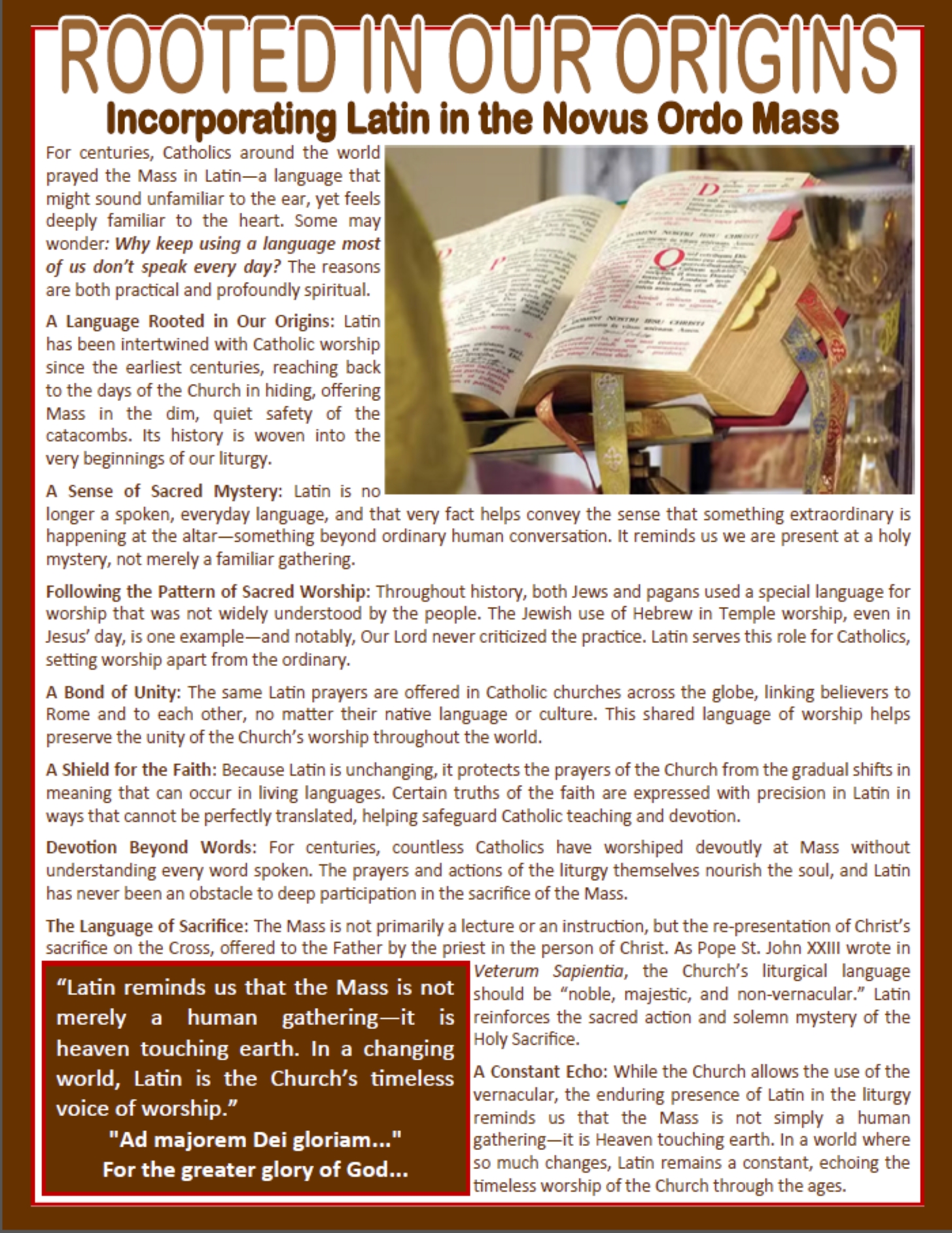

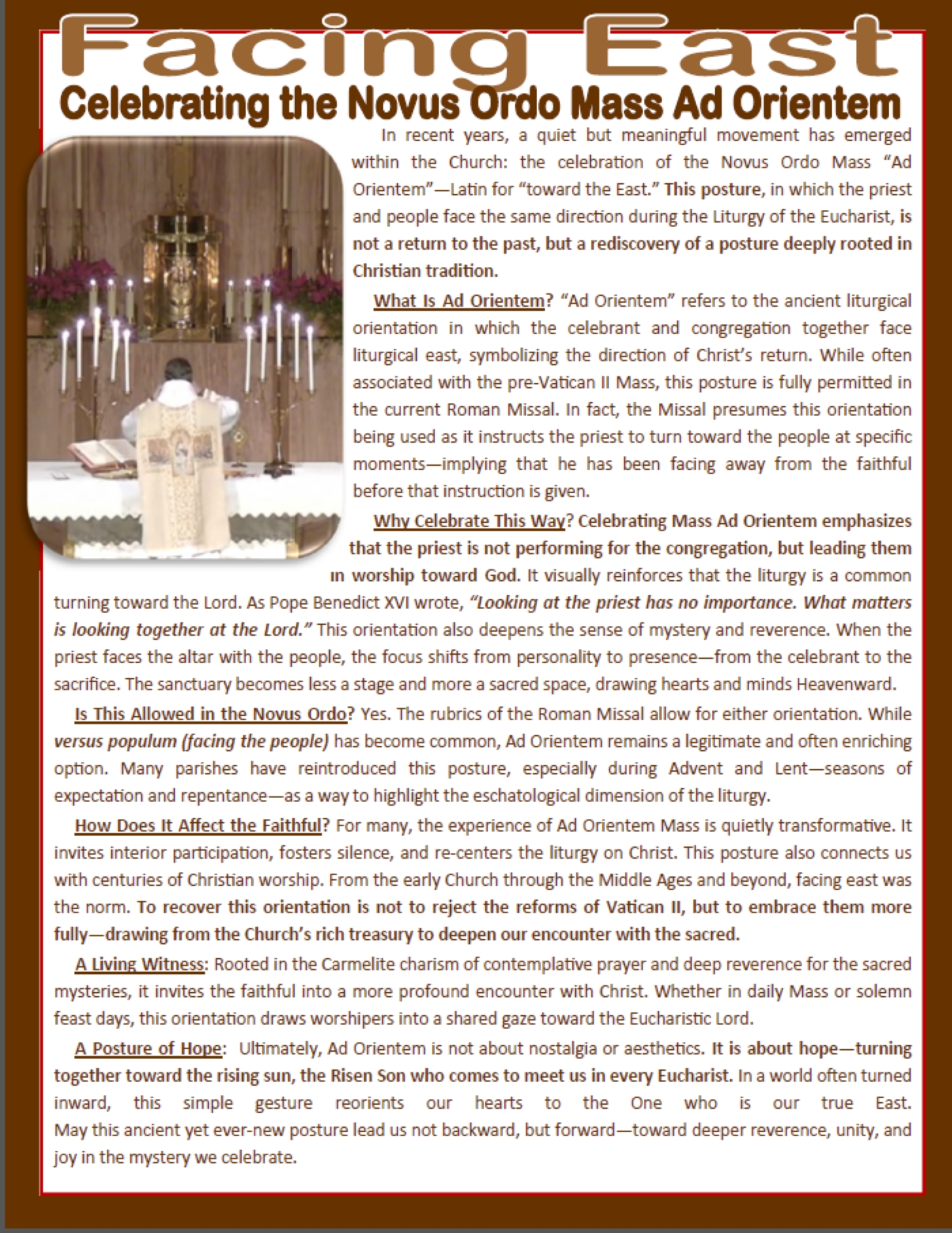

UNDERSTANDING THE HOLY SACRIFICE OF THE MASS